You can take the arts out of politics, but you can't take the political out of art

Column by Augusta Atla published in Kunsten.nu - 12 Oct 2023

Column by Augusta Atla published in Kunsten.nu - 12 October 2023

Over the past few weeks, as we have in Denmark discussed the blasphemy law, I have learned that the danish politicians are missing one thing: a one-week seminar - mandatory for all active members of the Danish Parliament - on the political wingspan of art in Western history and its active contribution to contemporary democracy. Politicians can start by reading this.

Since the dawn of time, art and politics have intertwined and have always gone hand in hand, also when it comes to the birth of Europe and democracy in antiquity. Everyone is familiar with the many ancient Greek sculptures from the Glyptotek in Copenhagen. The sculpture of the muscular male body was invented in antiquity to promote a very literal body ideal for young men to follow.

Along with the invention and hosting of the Olympics, these sculptures were meant to instill the desire to keep (the man's) own body strong and healthy. The young men of Athens had obligatory military service and could be called up for war at any time.

Theater was also invented by the Greeks to keep the democratic society, the human body and mind healthy. They called it 'Catharsis' and believed that drama, tragedy, poetry and comedy kept the people healthy and the peoples cohesion strong.

One of the largest amphitheaters of antiquity at Epidaurus was built on the sacred site of the medicine god Asclepius, which was the most famous sanatorium and healing cult of antiquity. The development of the theater, sanatorium and cult of Asclepius has helped shape our concepts of 'medicine' and 'hospital' - at the time, concepts that were completely inseparable from art.

Alongside the ancient hospital, library, baths, sports stadium and temples to Artemis and Asclepius was the theater. The theater hosted festivals for up to 14,000 people who watched drama, music, comedies and tragedies for days on end.

There were also competitions to see who wrote the best comedies and tragedies, and throughout the ancient tradition of art, healing and social order, the winners were seen as heroes.

Christianity as patron of the arts

After Christianity replaced the pagan gods of antiquity with one god, the theater became less popular as the focal point of a society for a period of time, and works of art now had to support the Christian faith and its ideas. The space of the church became the new 'theater' and drama was replaced by the text of the Bible.

Many of the masterpieces we know today from art history were created with the church as patron, setting and mediator. An example of how art did not have a free rein during the Renaissance is that hundreds of Botticelli's paintings were burned by the church (on the orders of Savonarola) because they still depicted pagan subjects. Botticelli's beautiful Spring (1480) is one of the few of his non-Christian works that escaped the church bonfire - perhaps because it hung in the private chambers of a Florentine merchant.

The new patron: the merchant and powerful families in Europe

Trade made Florence and Venice rich, and long before Italy was unified as one country, Renaissance culture used art to promote a family's wealth and to instill reverence for one lineage. Art history contains tons of portraits of Europe's aristocracy in all their splendor and power.

As trade grew in Europe, a middle class and a whole new elite emerged that were not aristocratic or royal, but merchants. This meant that art suddenly became the property of the merchant, free from the patronage and regulation of the church.

The French Revolution and humanism in Europe

With the growing social unrest in Europe and the French Revolution, art changed hands from those in power to the opposition. Delacroix's famous painting Liberty Leading the People to the Barricades of the French flag as the flag of the people in the midst of the revolution is a great example of how painting could be an asset in the revolution.

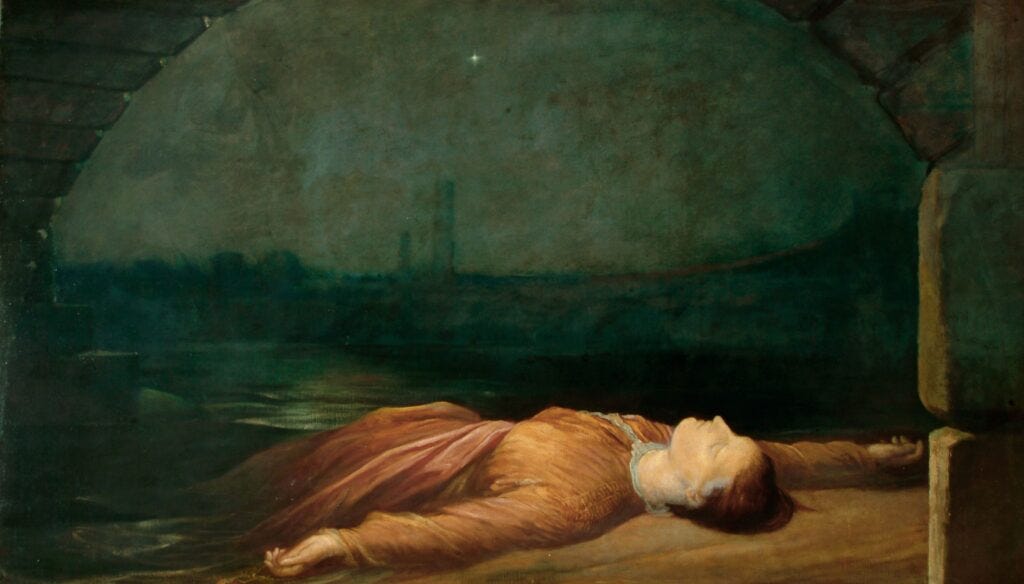

Can art improve the human condition and help shape the future? In the 19th century, Victorian artists increasingly began to believe it could. 19th-century artists painted images of the poor and their conditions precisely to address social injustices. The exhibition Art & Action: Making Change in Victorian Britain at Watts Gallery - Artists' Village (60 km from London) in 2020-21 described how painting functioned as political activism and how art in 19th century England was made not just to comment on, but to create better conditions for people.

Victorian artists used their art to develop strategies to confront the most pressing social issues of their time. They also participated in the debates of their time by using their positions as public figures to write articles in political journals, donate their artworks to charity auctions, design banners or posters for social movements, or paint scenes that addressed the country's most pressing issues.

The exhibition showed that art activism has Victorian roots, among other things. In Denmark, during the same period, we find similar socially engaged painters such as: L.A. Ring, Frants Henningsen, Erik Henningsen, H.A. Brendekilde and Jens Birkholm.

Similarly, many books in literary history were also created in opposition to those in power: James Joyce against Catholicism in Ireland, Charles Dickens against the harsh class society in England, and Martin Andersen Nexø's books about the plight of the poor and class society in Denmark around 1900, just to name a few.

Like Virginia Woolf, who not only invented entirely new forms of literary writing, but with her 1929 essay A Room of One's Own, used metaphor to explore social injustices and comment on women's lack of freedom of expression.

The democratic asset in contemporary art

With women's suffrage in the West around 1900-1920 and the admission of women to art academies in Europe during the same period, art also became an instrument of women's emancipation. Although there were female artists as far back as the 15th century in Europe - and we still haven't contextualized all the art theory and form semiotics that these works have created in history - this oppressed group developed a visual language using art as a method for their fight for equality.

For example, from Meret Oppenheim, Martha Rosler, Valie Export to Mona Hatoum, we see women's former domain, the kitchen, transformed into questions of power, weapons and symbols.

And artists such as Augusta Savage and Jean-Michel Basquiat have, through their art, helped to highlight diversity and alleviate discrimination in our society, both within the art scene itself, but also through the general public's encounter with their work.

Throughout the 20th century, art also moved out of museums and galleries and into public spaces, again to promote social change. And on the shoulders of Dada, Conceptual Art, Fluxus, Performance Art and Allan Kaprow's Happenings, a whole new genre was formulated by French art theorist Nicolas Bourriaud in his 1998 book of the same name: 'Relational Aesthetics'.

Unlike before, where the artwork communicated through aesthetic objects or through the artist's own performing body, 'Relational Aesthetics' was characterized by wanting to activate the participating audience. Today, this approach is completely normalized and many contemporary artists incorporate (consciously or unconsciously) this aspect into their art. Two of the most seminal artists in this field are Rirkrit Tiravanija and - in her own feminist way - Vanessa Beecroft.

This means that today, art is also socially engaged in a very literal sense, where the audience are direct co-creators of the work itself.

Art - the cohesiveness of a country

Whether art appears as a happening, as the artist's own body or as a fixed object or image, art is not only parallel to, but totally pervasive in human history and even takes part in the development of our culture and the invention of philosophy, language, medicine, science, military, democracy and identity.

In Europe, since World War II, it has been understood that both art and human rights can be abused in the hands of the wrong people, and therefore people have given freedom of expression and art free rein to prevent fascism from gaining ground again. Among other things, formulated in the European Convention on Human Rights of 1948.

I myself have lived for many years in England, France and Greece, and regardless of the politics and changing governments of the three countries, the general public spirit is that (uncensored) art has an important function in Western democracy.

In a democratic society, art - even today - can, like the theater of antiquity, be understood as the cohesion of a country. A population feels the pulse of its democracy, its country and the outside world through art. Together with art, we look again and again at our ideas, history and emotions. You could say that today, museums, art and music festivals, theatres, concerts, cinemas, TV streaming, books, libraries, radio and podcasts are a civilized way to engage people's voices, coexistence and connection to society.

Of course, a state can censor art and criminalize blasphemous art, even in Denmark. But to wring activism out of the essence of art is impossible - even if you wanted to. Art is created by man, and man is born political. Being a body - gender, class, ethnicity, nation, caste and sexuality - is inherently political. We know this from the history of colonization, working class and feminism, and from the debate on the rights of LGBTQIA+ people.

Blasphemy laws cause societal development to go backwards. In the long run, these blasphemy laws can actually have a negative impact on the cohesion of the population, set back equality and the rights of LGBTQIA+ people and create a general distrust of politicians.

More importantly - and what Danish politicians in this blasphemy law period overlook: You can't change an age-old tradition: the history of art. Visual artists (as well as musicians, film and theater directors, designers, architects and writers) are also activists with their works. And not just activist for a particular cause, but the very fact that the work is ambivalent, critical and (socially) engaging, and even without clear answers, makes it 'not just a pleasure', but a humanistic and democratic practice.

And it is precisely the works that touch a zeitgeist that go down in history as masterpieces.