Will People Ever Get Access to 'the Other Half' of Art History?

Column published in Kunsten.nu. 30 May 2023. By Augusta Atla

Column published in Kunsten.nu - 30 May 2023. By Augusta Atla

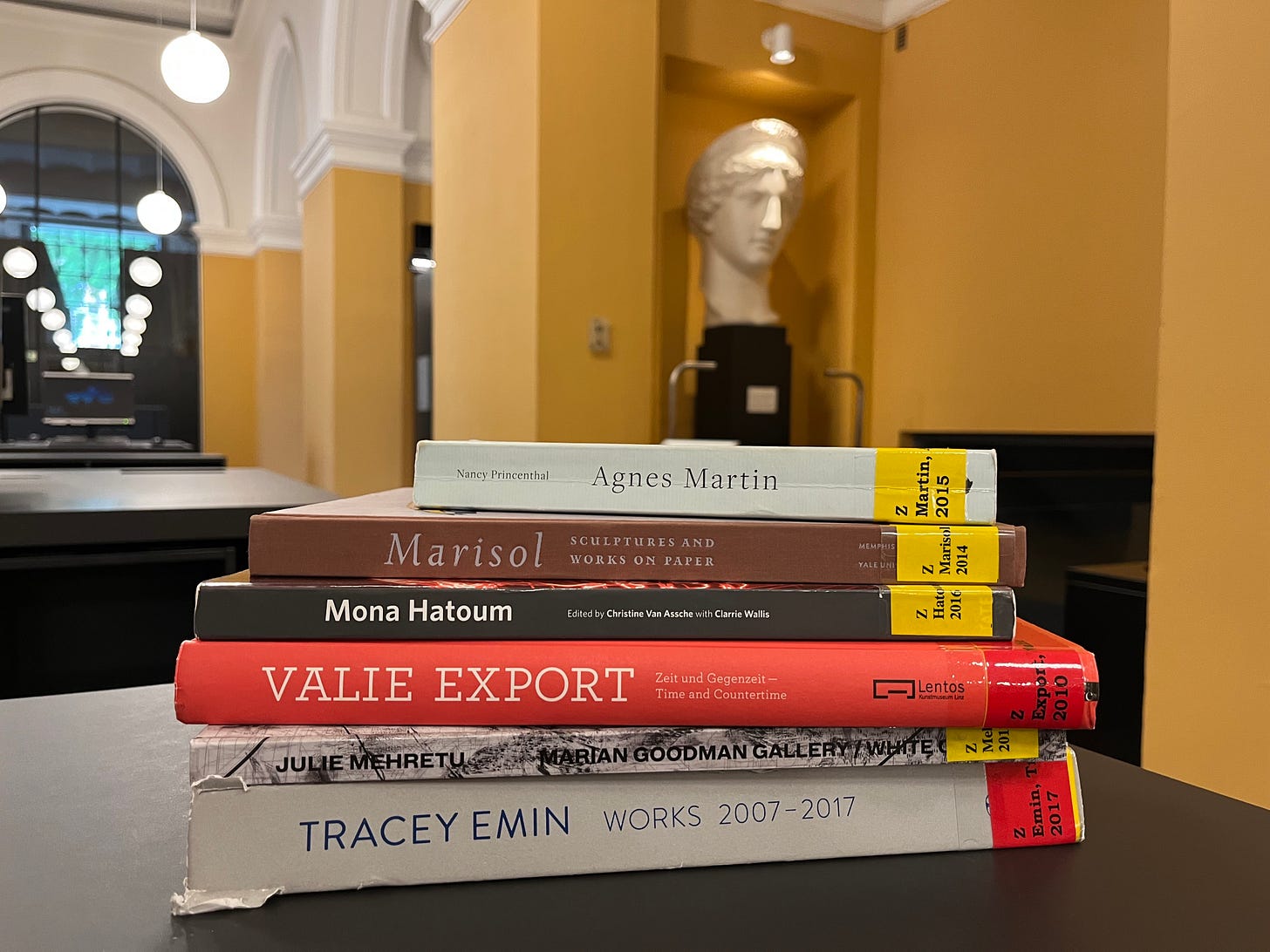

Books on women artists are at last being published, and in recent years we have been treated to exhibitions presenting this category of work that history neglected. But in libraries, there is as yet no ‘Women Artists’ category on the physical shelves. This is alarming.

This summer sees the release of a new non-animation Barbie film. This doll-cum-archetype was not the invention of Mattel. The doll dates not only back to ancient Greece - viz. the Venus de Milo - but also to the little ceramic dolls that children played with in ancient times. Barbie is a perfect image of the fact that, for millennia, our culture has been ‘a man’s world’, in which women were expected to be passive and subservient, and serve as muses (for men). Those women who, against all odds, were strong, expressive and even creative artists – do not yet feature in history.

As a result of the patriarchal imprint on art history and its method of exclusion, based on class, sexuality and gender, we still have an incomplete category of works - ‘Women Artists. 1500 to the Present Day’ - all waiting to be tracked down, archived and researched.

And where should that archival process take place? You guessed. The library. History is perpetuated and verified by those who curate, archive and tell the story: not only in terms of individual literary works, but also the information structure and architecture of the library itself.

Here in Denmark, we are still lacking a library with a section dedicated to ‘Women Artists’ in the Visual Art / Art History department. Yes, you can search for ‘Women Artists’ in the online database of the Royal Danish Library, but you still cannot find everything, because the ‘Women Artists’ tag is an all too recent addition. This means there are books you simply cannot find when searching for ‘women artists’, if you do not know the name of the artist you are looking for. It makes exploring the collection intensely frustrating. Ironically, it is names of female artists that the general public still know very few of.

It is a bit like an archaeologist coming to a Greek island and discovering a whole new era of objects. But instead of excavating them, they simply choose to cover them up in soil, saying: “Let’s just leave them down there.” That would be impossible in the professional world of archaeology, but that is what we are still up to in Denmark when it comes to the ‘Women Artists’ category.

There are many superb female artists in history (even names we do not yet know) and who have not yet been ‘written into’ the history of art. That is exactly why, in 2014, the art historian/curator Camille Morineau not only established and founded a digital, online, open archive of female artists, but also created a physical library, Aware in Paris (Archives of Women Artist Research & Exhibitions), which is open to the public. Aware is funded by the Chanel Foundation. The biography section of the library was created in collaboration with Le Dictionnaire universel des créatrices, a collection of volumes featuring 10,000 biographies of creative women, published in 2013 with the support of UNESCO.

How are we in Denmark and the other Nordic countries supposed to learn about all these works by women artists, if we do not objectively and meticulously archive them in a single category - not only in the database on the library’s internal search system, but also in a place where the public have physical access to them?

If this category is only available as an online database, we cannot explore its riches in an inspiring, aesthetic and straightforward manner as we would do in a physical library. The art historian Aby Warburg (1866-1929) also believed in the importance of the physical library and invented the phenomenon ‘Law of the Good Neighbour’, in which one categorised different time periods according to cultural anthropological phenomena.

The idea was that it was not necessarily the book you are looking for that would prove most important in your historical research, but the book next to it. Similarly, a Women Artists category would be a totally refreshing and new way of exploring art history. You could call ‘gender’ a Warburgian category that even the Warburg Institute in London has not yet implemented.

You could say that, on a global level, this category is like a sudden deluge, so requires extraordinary accommodation and archiving in order for us to have a new clear picture of history.

Right now, we are still trying to comprehend a new category. Once the pieces have more or less fallen into place, and the category has been better defined, art history will reshape, change its overall image and introduce new descriptions of ‘the canon of art’, modifying definitions of genres and even minting brand new genres.

This is already happening. 20th-century textile works are now accepted as ‘fine art’ - for example, pieces by Sonia Delaunay or Hannah Ryggen - works that would not have had the same status as those of men in their day.

Or take Hilma af Klint. On account of her abstract works from 1906, she has now replaced Kandinsky as the acknowledged ‘inventor of abstract art’. The documentary Beyond the Visible looks at the significance of Hilma af Klint for art theory.

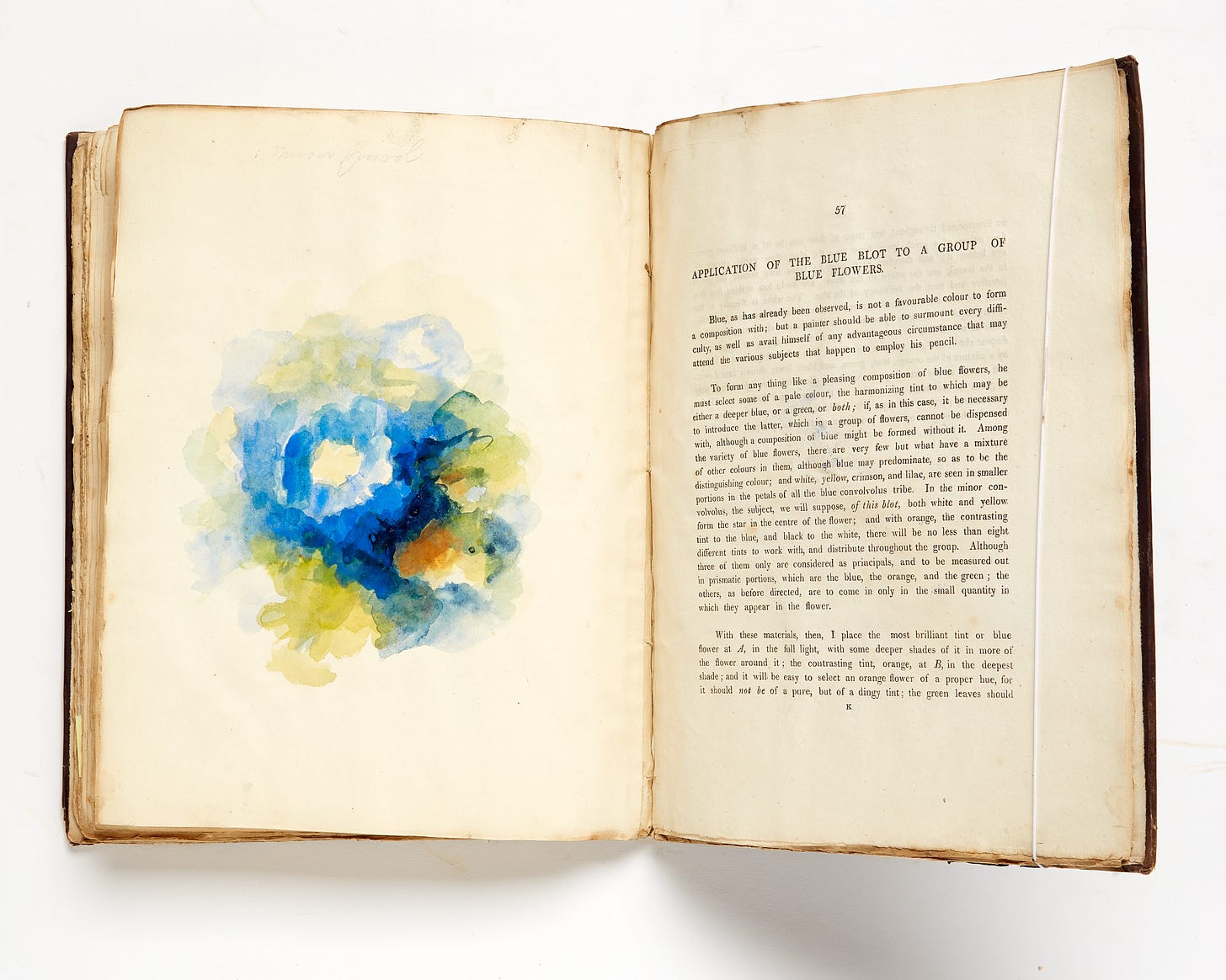

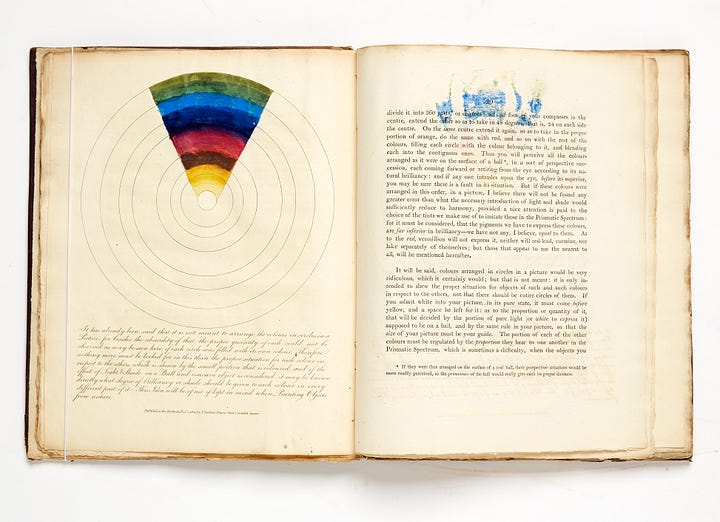

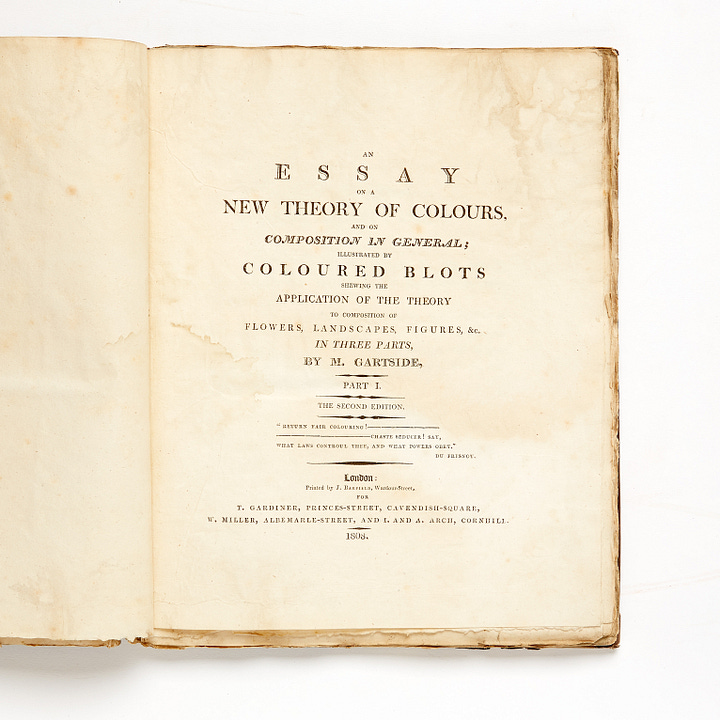

Meanwhile, Mary Gartside wrote and published theories of colour before Goethe did, and in 1902, long before Josef Albers, Emily Noyes Vanderpoel published her pioneering book, Color Problems: A Practical Manual for the Lay Student of Color (1902).

In the long term, there will be many such examples. Also outside the ‘Women Artists’ category, women appear, who helped create art history as co-artists in the production of masterpieces or as studio managers for the great masters of Western art history. Four Women who Helped Shape Art History, a public engagement/interpretation project at the National Gallery in London, spotlights this very subject.

How do we get this new category – ‘Women Artists’ – not only to adjust the field of art, but also to open our eyes to this new picture of our cultural history? The answer? To democratise and demonstrate this new category in libraries.

In practical terms, we (in Denmark) need an extraordinary grant (from the State) to the Art Library of the Royal Danish Library to purchase duplicate copies of the books already on their non-gendered shelves books published after 2006), and then find one or more shelves dedicated to this category.

The best solution would be a permanent categorisation physically, given that the concept of binary gender does not change – as far as the past is concerned. Art history was already curated on the basis of gender - with ‘Male’ as the only gender highlighted. The idea is not to fixate gender as binary, as history has always done, but to re-archive history as it should have been archived, by rendering visible what was excluded for millennia.

Of course, the category should not only include cisgender women, but also transgender, double-sex, intersex, fluid gender identity, and non-binary.

Going forward, the category should be titled ‘Women Artists+’. The category should include artists who perceive themselves as gender-neutral and polysexual.

The Women Artists+’. category would thereby cast light on the methodology of patriarchy and sustain a critique of it, expanding the focus and debate on gender in general – also for the future.

“Hope for the unknown is good, it’s better than hatred for the familiar” is one of the lines in this year’s Oscar-winning film, Women Talking, directed by Sarah Polley. Similarly, we cannot slow down humankind’s love of knowledge and a total rethinking of the method by which we make history.

This mediating, innovative archive could be located in The Black Diamond in Copenhagen for a limited period of time as a kind of exhibition, before moving on to permanent shelves at the National Art Library in Nyhavn.

I am convinced that people would flock to these shelves, especially if the exhibition was mounted as an event in its own right.

Why should the ‘Women Artists’ category only be for researchers, art historians and visual artists? Why is it important for people to get to know this new category?

Firstly, so that young people can see themselves in the prowess and achievements of all these women – a truer picture of the accomplishment of the sexes in the history of art. Secondly, it will keep people updated on a global level about what is being retrieved from history, and researched and exhibited abroad. The population will then be included in this global revolution and gain insight about the backdrop of the museums' work.

We will thereby applying indirect pressure on museums in Denmark, urging them to no longer exhibit a repertoire of predominantly male, classical artists - as many of them still do!

This would also shift our mental archetype of the ‘genius artist’ as being male to being multi-gendered. This would be an extremely important change, because Denmark is still suffering from Jorn, Pollock and Picasso syndrome.

When will we have museums dedicated to individual women Danish artists? Isn’t it time for a Sonja Ferlov Mancoba museum? Or a Franciska Clausen museum?

In England, at Goldsmiths Library in London, since 1983 there has been an artist-initiated project - the Women’s Art Library. It collates works (DVDs, CDs and digital files) and publications submitted by artists themselves, while also serving as a feminist forum for debate within the art profession.

The creation of this archive - as a kind of feminist work project under the auspices of the library - was partly the brainchild of the artist Monica Ross (1950-2013). The archive still exists today and is open to the public.

And The National Gallery in London already has a physical shelf dedicated to ‘Women Artists’.

A library section like this does boost the level of professional art, enormously - and in terms of ‘gender research in the visual arts’ - creating more debate and focus on LGBTQIA +. We would arrive much quicker at a new history of art and ensure a national archive of all those who never featured in it.

This categorisation of the past in the art libraries of the world will be totally normal in the future. After all, no matter how we understand or classify gender today or in the future, the classification has historically been made on the basis of gender.

So what will we do later? Well, that depends on whether we ever get equality.

We could introduce a BC/AD into art history. The year 2100 could be the start of a new era, in which the 'Women Artists+' label would be only applying to books and publications pre-2100. That is to say, when it comes to art history, the traditional method of selection will not change in the course of time.

Let’s say after the year 2100, if we are not going to have a ‘Women Artists +’ category for books and publications post-2100, then we are yet to undergo a fundamental and wide-ranging change in the West. We need to rethink the whole world in terms of everything from medicine, priesthood (religions’ power positions) and free abortion to political and capitalistic power.

In other words, regardless of “if” and when we arrive at that hypothetical new era - we must start archiving history accurately and finally put an end to discrimination.