The Superhero of Gender Equality: Barbie

Column published in Kunsten.nu - 9 August 2023. By Augusta Atla

Column published in Kunsten.nu - 9 August 2023. By Augusta Atla

#genderequalitysuperheroBarbie

Greta Gerwig’s Barbie is the pink breakthrough that both the film industry and art and culture throughout the world needed. The film looks at the construct of gender and cements women’s freedom of expression by painting the world pink, piercing the taboo of what art is NOT supposed to look like: feminine, girly and pink.

It seems that no one had expected the Hollywood film Barbie would spark the cultural phenomenon known as the ‘pink movement’ and break all world records. I am certain that even one of Elon Musk’s space satellites has detected Barbie’s pink. Perhaps people had forgotten that 50% of the world’s population are (or have been) girls? So, the question is what impact can Barbie the movie and the Barbie phenomenon have on contemporary art and visual culture?

Just 17 days after the film’s premiere, the films global earnings earned Barbie membership in the exclusive billion dollar club. Prior to that, there were 28 male director members in the film industry’s billion dollar club; now there is a female director – Greta Gerwig.

What is ground-breaking is the fact that the film proves you can make (a hell of a lot of) money from a brand new audience: so far, 65% of the film’s audience have been women and girls. What is also radical is how the script creates a universe based on the history of equality and gender – something I have never seen a film do before.

Barbie is a fantasy comedy told as a legend, in which the Barbies are in a way ‘gods’ in Barbieland: a place where everything is always good (for them). Here they are the supreme leaders and know nothing about sexual objectification or sexism against women. They are Barbies: superheroes for girls.

Barbieland is a kind of sci-fi god matriarchy. The plot is based on the simple fact that girls in our world see themselves in Barbie the ‘super hero’, learning to regard themselves as something other than mothers or wives, thereby being trained for equality in their later lives.

The protagonist Stereotypical Barbie journeys into the real world to find and stop the person who is playing too hard with her. This leads to problems even within the otherwise protected territory of Barbieland. In the space between the image of our playing and the world of reality, we follow Stereotypical Barbie on a journey of development, and Margot Robbie plays the role so well that we gradually see Barbie with her own soul, just as we invested her with a soul when we played with her as children.

Even though the film is bound to sell Barbie dolls, in Greta Gerwig’s hands it is more than just an advertisement for Mattel. It resonates across the entire world culture – regardless even of religions: from Mexico to the UK, from Australia to China, the film is a hit. The success of Barbie lies in the very fact that we do not yet have gender equality – even in Denmark.

Malala Yousafzai – a Pakistani Nobel laureate, human rights advocate and feminist – has posted a photo of herself on her Instagram profile in an outsized Barbie doll box, thereby stressing how important this debate still is.

Gender Equality in Hollywood

Information from the US organisation Women in Film reveals that only around 14% of top-earning Hollywood film directors are women. The fact that a female director and an audience comprising 65% women can earn so much money is an event in itself and will improve work opportunities for female directors in the future.

There is no doubt that Barbie will also pave the way for an increasing number of new types of films featuring female protagonists and new narratives about women as the focal point: something to which more and more film production companies run by women have been devoting their activities. Just take Reese Witherspoon’s company Hello Sunshine and Margot Robbie’s LuckyChap Entertainment. As it happens, the latter was one of the co-producers on Barbie.

How refreshing to watch a fantasy film about Barbie rooted in completely new (girl) worlds and with an entirely new perspective. Think about the infinite array of sexist narratives in film history, ranging from Pretty Woman to The Godfather. Actually, I cannot think of any film scripts that aren’t rooted in a patriarchal view of the world. Even though feminist ideas do exist in the films of Lars von Trier and Ingmar Bergman, women still flail around and suffer in the patriarchy.

And why all the debate about the film’s soft male roles and matriarchy? It’s a film. It’s art. It’s comedy. No one I know has ever accused Monty Python of being politically incorrect; everyone knows it is a comedy and that John Cleese is a comic actor. So what is people’s problem with Barbie?

Barbie has, for once and for all, nailed women’s entrée into the film industry. And opened up a completely new, extremely important portal in the Hollywood galaxy: gender equality.

A Girl’s Bedroom v. a Boy’s Bedroom

In my opinion, Greta Gerwig is the Joan of Arc of the film industry and visual culture. Yes, both the Barbie doll and Barbie the movie have their origin in the world of mass consumption and capitalism, but unfortunately this is the only way for female artists – once and for all – to gain respect in the world of film, breaking the glass ceiling in terms of revenue and producing films that rank alongside blockbusters such as Mission: Impossible, The Super Mario Brothers, Top Gun, Spider-Man, The Avengers and Star Wars.

We live in a very one-sided cinematic world, in which the most profitable films pretty much only depict the play universe of boys. So, Barbie paves the way for a new yin and yang balance in the box office machine. In its own mathematical equation, the Barbie doll itself is about the same thing – equality. So, in a strange way, everything adds up.

With an already invented back catalogue, Mattel has launched their new feature film business. The next film in the Mattel pipeline is Polly Pocket starring Lily Collins.

The Pink Movement

Just as Taylor Swift’s fans managed to create a small earthquake during a recent concert, so too can Barbie the movie shake up norms about ‘what art should or should not look like’. For the new generations, being feminine and feminist is not a contradiction. We are not afraid to be feminine; we can own the male gaze and play with culture’s notions of gender. This is also one of the main points Barbie the movie underlines.

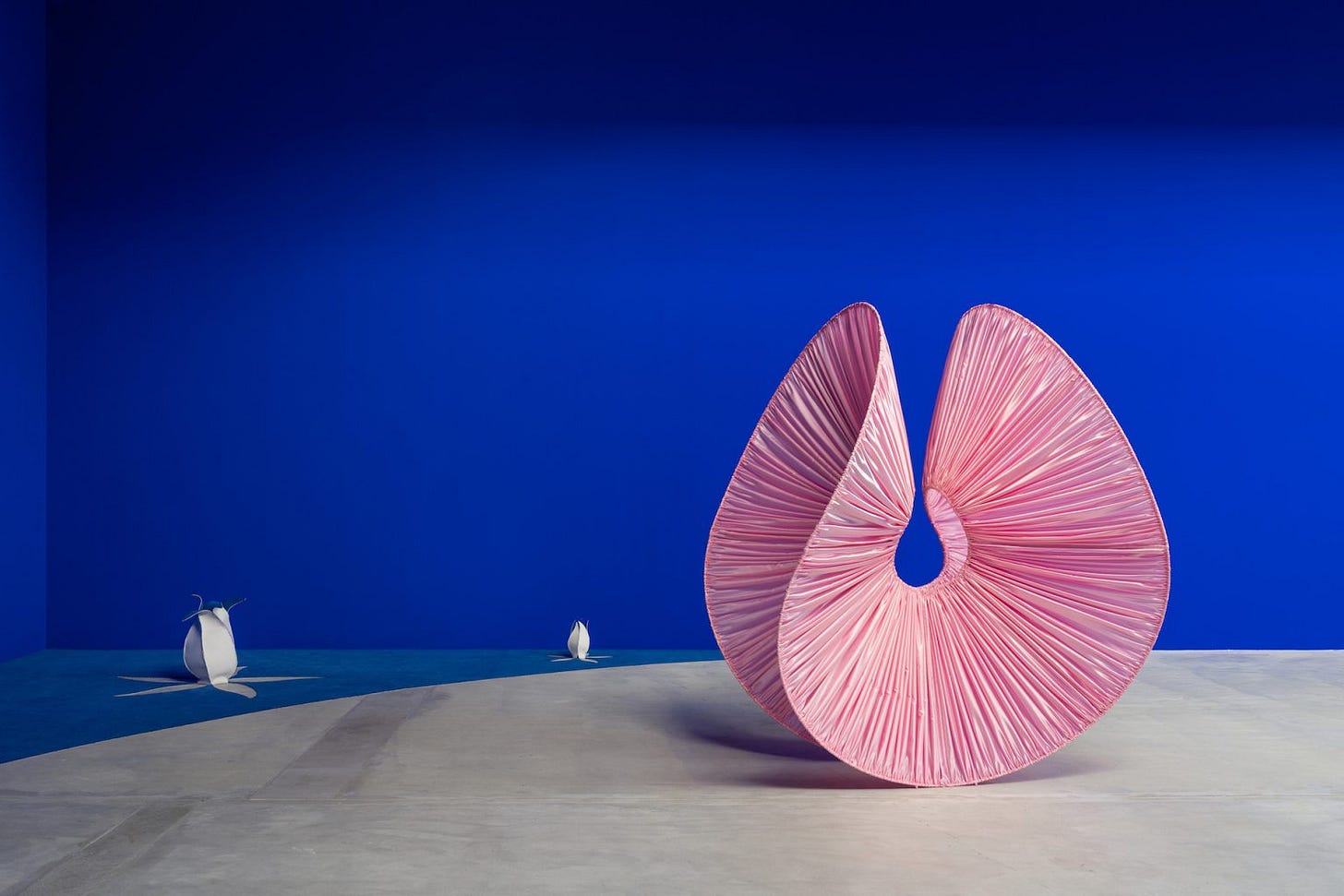

My former teacher in London, Monster Chetwynd is an artist who has provided us with images of the sacred, free space in which children play. Her artistic practice is not afraid of ‘girl’ taboos, animating the world in free juxtapositions of images, just as a child animates dead objects.

Likewise, Greta Gerwig also spent ages trying to find the right pink for the film’s set design. As she put it in an interview, first she had to transcend the constrictions of adult taste and only when she let go of those adult norms did she come up with the genuine pink universe that Barbie inhabits. The same can be said about Chetwynd: she enters the game wholeheartedly and for a while abandons adult logic.

Examples of other international visual artists who play with girls’ play are: Lily van der Stokker, Karla Black (nominated for the Turner Prize in 2011), Sylvie Fleury, Pippa Garner, Francesca Woodman, Marisol, Chantal Joffe, Newsha Tavakolian, Anna Weyant and Isa Genzken, whose work is featured this year in an exhibition at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. Not forgetting Danish artists such as Tove Storch or Eva Steen Christensen (whose work currently features in an exhibition at Arken).

The Didactics of Gender Equality

The intentionally political thing about the invention of Barbie in 1959 is the fact that she did not get married and give birth: something we totally understood as children. We followed Ruth Handler’s (Barbie’s inventor) exhortation and imagined our independence in the real world of the future in roles outside marriage and motherhood. Barbie was intended as a tool for women’s liberation.

Because we do not yet have gender equality in the real world; we have Barbie in various liberated and prestigious roles and a variety of top career positions of which the doll helps us dream. The Barbie doll had her own dream house in 1962, when in the real world it was still very difficult for women in the United States to take out a bank loan. Barbie went to the moon in 1965, while NASA had no female astronauts until 1978. It would be a pretty sad outcome if we never achieved in the real world what the Barbie doll does in the world of our imagination.

Greta Gerwig’s film shows how, even though heterosexuality remained the brand we all grew up with, it also provided us with a tool that enabled us to play with the concept of gender. Barbie provided us with an image and a ritual with which to explore Judith Butler’s concept of gender performativity. We learned to step back and look at the construction of gender. I am sure that this is the reason for the success of Barbie the movie: the millions of girls and women who remember and acknowledge how they played ‘performing gender’ and learned to behave critically in the patriarchy of the real world.

We also learned to hate or love (or both) the Barbie doll for her male-gaze-based ideals of beauty. But such ideals of beauty cannot be attributed to Mattel alone; they date all the way back to ancient Greece. Even the ancient Egyptians had make-up – something the sculptures of Isa Genzken also spotlight. The film also shows how Mattel updated the doll with literally 100 new skin tones, along with new body sizes and body types. In the film, Hari Nef plays one of the Barbies, flying a very important flag for LGBTQIA+ and fitting brilliantly into Barbie’s new, updated universe.

The Warmth of the Film – the Inner Child and a Story of Development

What is moving about Greta Gerwig’s film is the fact that it is a declaration of love for girls’ play. According to Greta Gerwig, she herself played with dolls until she was 14 years old, and the fact that she just did not laugh AT the doll, but WITH the doll can be felt throughout the film. This is precisely what makes the film brilliant. It ends up as a universal work about humanity, about play – the sacred space of a child, and about the history of gender and the didactics and development of gender equality.

It is a heartfelt depiction of how we saw ourselves in Barbie. Ken (in the movie) is simply the result of the fact that girls did not see themselves in the Ken doll. He is, therefore, superfluous in Barbie Land: quite literally for the girls who play with him in our world. The film has just transformed this into a comic Ken plot. The funny thing about the Ken character stealing the scene in the film is that I don’t even remember playing with my Ken dolls, even though I think I had at least two.

The film reminds us of our (girls’) play, making it feel very familiar, intimate and tactile. When I watch the movie I can smell my childhood. It must also be a bit of an eye-opener for certain (curious) men (especially fathers of girls?) – a kind of a glimpse of the universal or archetypal nature of the play universe of girls.

In the real world, when we outgrow Barbie, and the game ends for us ex-Barbie users, we discover that the world is (still) full of gender discrimination. So, the film ends with Barbie’s visit to the gynaecologist and describes her loss of innocence. The sugar-sweet aspect of Barbie the movie is not sugar-sweet at all. In its own trenchant way, it poses a painful question about the stigma of gender, the shame of being a woman that many young people feel when they first go to the gynaecologist and their right to control their own reproductive organs in 2023.

All in all, Greta Gerwig not only sends Barbie and Mattel skyrocketing into the orbit of the film industry’s billion-dollar club, she also paves the way for much increased earnings for women directors in Hollywood, unearths a brand new female audience, invents a new language for millions of girls around the world for their play and for the social constructions of gender (#patriarchy) and flies a flag for the anarchic, free nature of comedy, also celebrating the ownership of women and LGBTQIA+ of their bodies.

Barbie the movie cements women’s freedom of expression by painting the world pink, piercing the taboo of what art is NOT supposed to look like: feminine, girly and pink.