Column by Augusta Atla in Kunsten.nu

COPENHAGEN, Denmark.

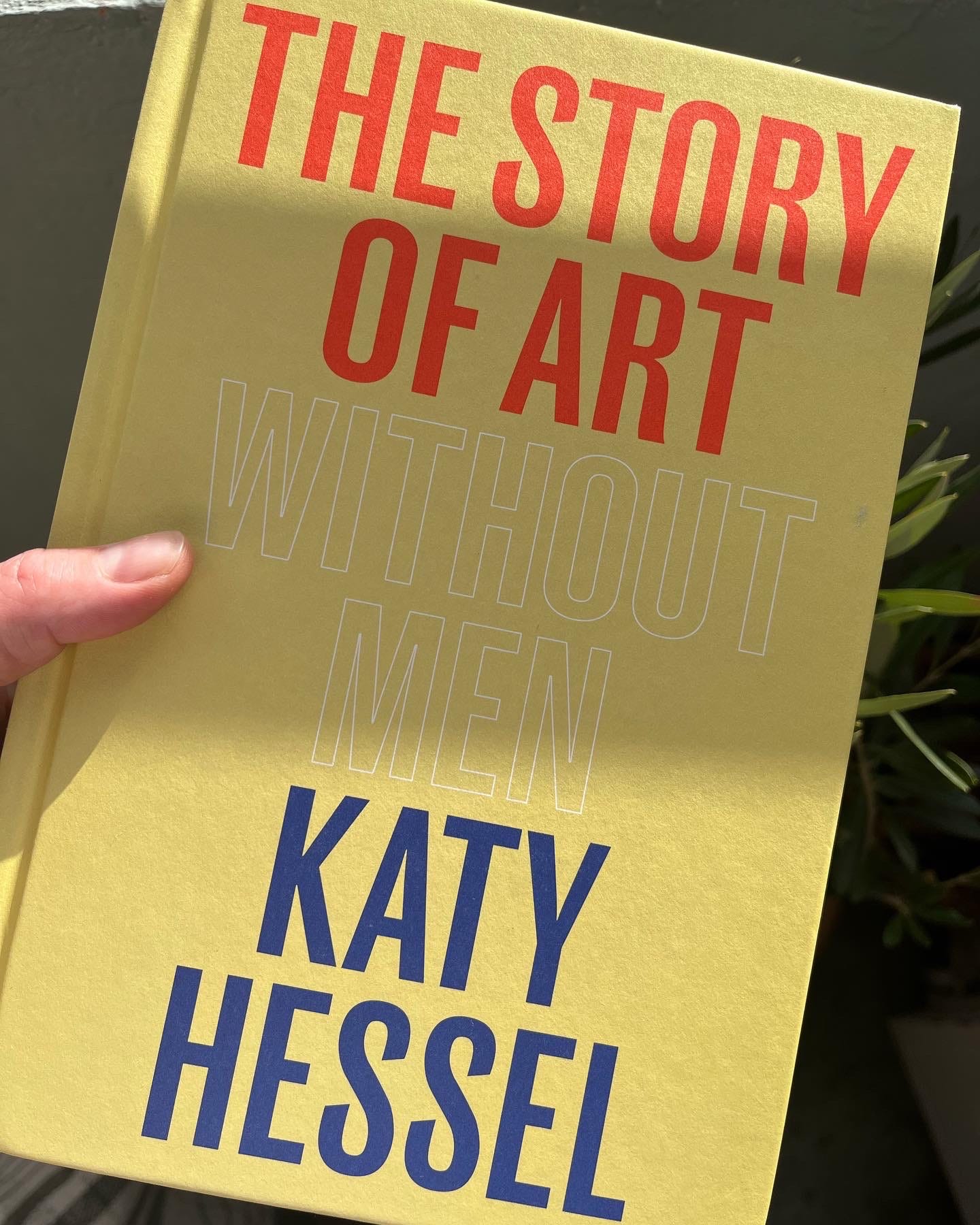

Finally this year, the book we were lacking arrived. In her book The Story of Art Without Men, the art historian Katy Hessel tackles the question of whether art history has been properly archived and written. It is not merely a much-needed update of art history with the inclusion of female artists. It also supports and develops a sustainable democracy, firmly rooted in equality, diversity and freedom of expression.

Freedom of expression, diversity and equality are the cornerstones of modern democracy. We should be able to speak freely and every single vote in an election should be treated equally to keep a democracy healthy and alive. The more people who vote in a general election, the more a government represents its country’s people.

If we did not have freedom of expression, our culture would have neither a representative government nor diversity in cultural debate, dialogue and solutions. Indeed, it could be said that a democracy without freedom of expression is no democracy. As we do today, the Athenian democrats of antiquity believed that democracy was inextricably linked to the ideals of freedom and equality.

With their acquisition of works, changing exhibitions and permanent collections, art museums help to write the history of a country and its culture. This can hardly come as a surprise. But the function of today’s art museums extends beyond this. Most museum professionals in Denmark – and the West in general – will agree that European, post-World War II art is based on artists’ freedom of expression. Moreover, today, via its public, collective use and repertoire of works created on the basis of freedom, an art museum actually serves to express the virtue of freedom of expression, thus making it a strong symbol and asset in democratic society.

The Agora of ancient Greece – the shopping mall of the time – was not merely a market for the exchange of goods and products. It was also a place where people shared thoughts and public political and philosophical debates took place. Similarly, one might say that today’s art museums are public gathering points, which provide space for culture to look at itself and for cultural debate, inspiring us to come up with new ideas.

However, unfortunately, given the perpetuation of old bourgeois notions of class and gender, the museum industry both in Denmark and abroad is still behind the times. Its acquisition of works and permanently exhibited collections are gender biased. Simply because the elite of the art world are weighed down by books containing old-fashioned ideas about gender and patriarchy. The exciting task of both this generation and of generations to come is to rethink the hanging of works from museums’ collections and to develop new strategies for the future acquisition of works.

It is not only the history of art that a museum’s permanent collection recounts. It also conveys (more or less unconsciously) a period’s views on gender and attitudes to issues of race. Today, we can easily adopt a critical stance vis-à-vis the narrative of art history, and examine the ideas with which it is curated and ranked. Several museums have begun to do this.

Fortunately, in various countries there is a growing focus on diversity, inclusion and new genre descriptions. The sooner this can become the ‘new normal’, the sooner museums will catch up with the times. Then art museums can finally become vital gathering points and muses for democracy – not only in terms of freedom of expression, but also in terms of that other cornerstone of democracy: equality. When it comes to art, that means equal treatment of quality, regardless of gender

The Italian art historian/artist Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) was allegedly the first person to write down artists’ biographies and one of the first art historians in the world. His book Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori (The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects) (1550) is regarded as one of the most important books in the history of art. The first edition described 142 artists, one of whom was a woman: Properzia de’ Rossi (1490-1530). This can hardly come as a surprise to anyone.

In Italy there is an organisation called AWA (Advancing Women Artists), which finds and restores works by women artists in Italy who have never received attention. AWA identifies, restores and exhibits works of art by women in the storerooms of museums in Florence, thereby bringing them to light. They include works by Plautilla Nelli (1524–1588), whose Last Supper is coming to be regarded as equal in quality to the famous work by Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo da Vinci featured in Giorgio Vasari’s book. Plautilla Nelli did not.

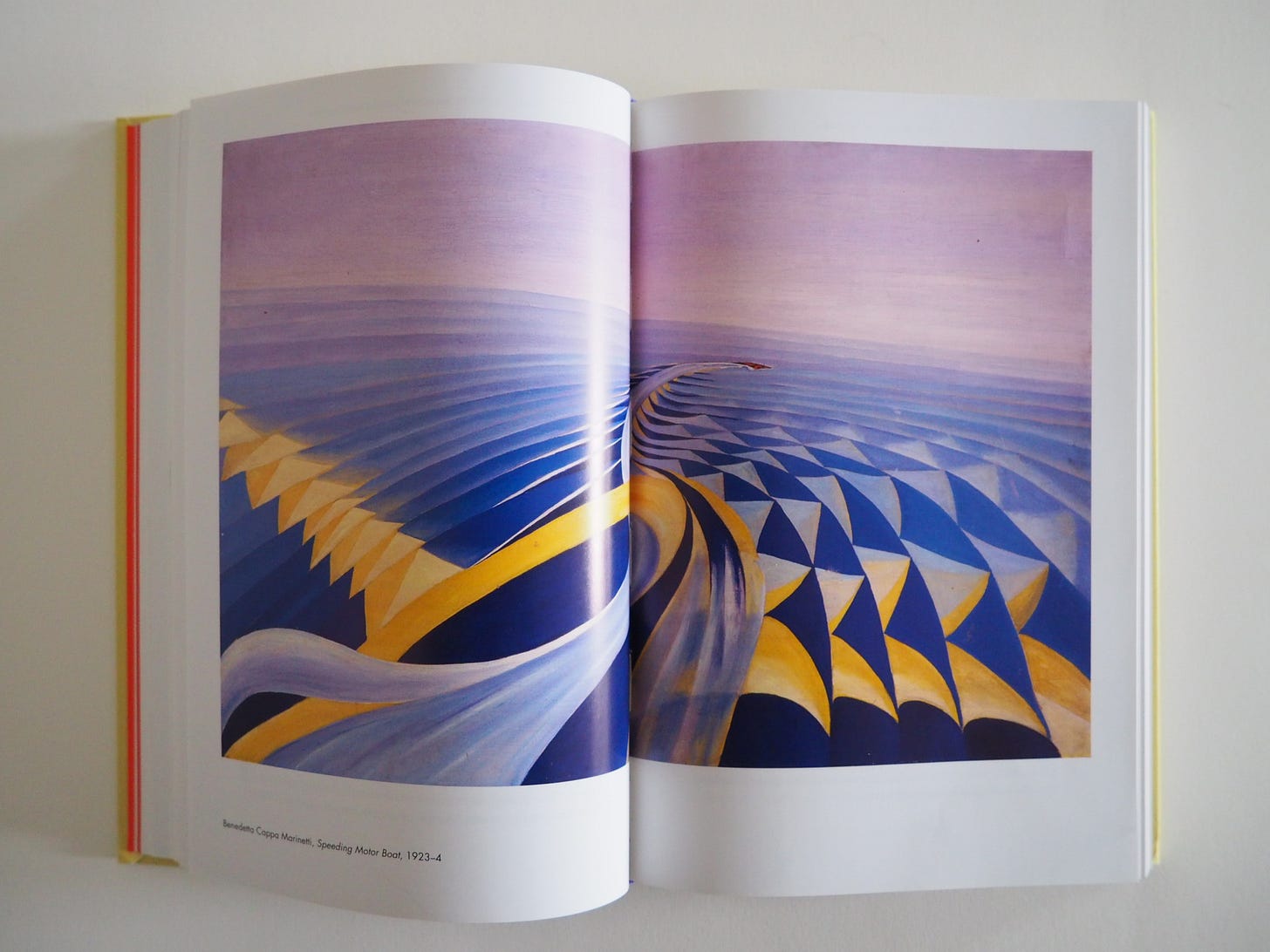

In 1950, the art historian Ernst Gombrich published The Story of Art. In its first edition, this review of the history of world art contained not one single female artist. In 1950, several female artists could have been included: for example, Janet Sabel (1893-1968), whose exhibition Milky Way (at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery in 1945) is believed to have inspired Jackson Pollock’s drip painting, Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986), Frida Kahlo (1907-54), Bernadetta Cappa Marinetti (1897-1977), Berthe Morisot (1841-95), Maria Sibylle Merian (1647-17171), Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) (who in her lifetime earned more money from her art than Rembrandt), Elisabeth Vigée le Brun (1755-1842) (a favourite artist of Marie Antoinette) and Hilma af Klint (1862-1944), to whom the Guggenheim Museum devoted a solo exhibition in 2019. These are just a few.

Finally this year, the book we were lacking arrived this year. In The Story of Art Without Men, the art historian Katy Hessel addresses the issue of whether art history has been properly archived (purchased for museum collections) and written down. It is not merely a much-needed update of art history with the inclusion of female artists. Due to the new works that should be included it also contributes to a brand new understanding of art.

After reading the book, and given my own geeky insight into the works of female artists, I thoroughly recommend the book. Anyone involved in art should read it. All women and LGBTQIA+ persons should read it. All children should have it read to them. I hope it will be translated into Danish and will be on the curriculum - even in primary school. Hopefully, they will make a children’s book version of it and even turn it into a BBC documentary. We can only hope. Meanwhile, at least it has been a bestseller in the UK. Maybe it will end up being translated into many languages and become a new classic. At least for a while, until more people write more about female artists.

Even though the book does not go into depth or provide a brand new understanding of art, Katy Hessel’s book features an excellent timeline, listing more than 300 works by female artists from 1500 until today. In her account of history, Hessel chose to use excellent, amusing anecdotes about the artists’ lives: for example, how Marisol (1930-2006) was more famous than her friend Andy Warhol in the 60s, and her exhibition at the Stable Gallery in New York in 1964 received up to two thousand visitors a day. The entertaining anecdotes mean that the book is easy for everyone to read and is clearly aimed at a wide audience. This is important. When people are informed, this indirectly compels museums to keep up with the time, so they do not end up as menhirs to obsolete knowledge.

Of course, one can sense that the book is written in an Anglophile (UK & USA) tradition that colours the author’s selection of artists. It includes only four Scandinavian artists, none of whom are Danish. But that is fine. That paves the way for other versions of art history from other parts of the world in the future. I am sure they are already in the pipeline as I write.

Although I am by no means a general reader, the book featured several artists of whom I had never heard before, and whom I was more than happy to get to know: Ellen Harding Baker (1847-1886), Angelica Kaufmann (1741-1807), Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973) and Loïs Maillot Jones (1905-1998).

One of the museum exhibitions that has already took a similar view of art history was the famous elles@centrepompidou at the Pompidou Centre. For two years (from 2009 to 2011), the hanging of the permanent collection featured exclusively works by female artists. Many of the works had been tucked away in the cellars of the Pompidou Centre and had never seen the light of day. In other ways, the museum simply put its own practice and archives under the microscope.

Alongside the curator Camille Morineau, who came up with the idea of elles@centrepompidou, Maria Balshaw, current director of the Tate art museums and galleries, is a major player in the world of art, when it comes to the promotion of diversity. In 2019, in the galleries of the permanent collections, the Tate presented the exhibition Sixty Years, which painted a comprehensive historical picture of the UK’s own female artists.

Since her appointment as director of the Tate in 2019, Maria Balshaw has presented solo exhibitions of work by major female artists such as Paula Rego (1935-2022), Anni Albers (1899-1994), Cornelia Parker (1956 -), Maria Bartuszová (1936-1996), Sarah Lucas (1962 -), Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017), Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962), Dora Maar (1907-1997), Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012), Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943) etc. etc. The Tate has also devised LGBTQIA+ tours: guided tours of the Tate’s permanent collection, taking a special look at works tackling gender and sexuality.

2023 will see the opening of the exhibition Art, Activism and the Women’s movement in the UK 1970-1990. The first of its kind, it will be a major investigation of works of art by more than 100 female artists working the UK between 1970 and 1990. Denmark has never seen this kind of exhibition, spotlighting Danish and Scandinavian the 1980s and 1990s (or even from the 00s until today). I hope it will serve to inspire the people who run our museums in Denmark!

Other museums of art history that are also rethinking their exhibitions and collections include the Prado Museum, which included more several female artists in their permanent collections in 2021. In 2021, the Gallery of Honour at the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands included more female artists in their permanent collections, while the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC has allocated $10 million for the purchase of works by female artists to cover some of the gaps in their collection.

Founded by Grażyna Kulczyk and opened in 2019, Muzeum Susch in Switzerland focuses mainly on works by female artists, currently presenting an exhibition of extremely beautiful works by Heidi Bucher.

Several countries have already established prizes for women artists in an attempt to change old habits: Sackler Center First Awards, PRIX Aware, Max Mara prize for women, for example.

Something similar is also happening in other artistic industries. Reese Witherspoon is leading the way Hollywood with her film production company Hello Sunshine, which produces films and TV series with women as the main protagonists. They include: Big Little Lies on HBO, The Morning Show on Apple TV, Surface on Apple TV and Little Fires Everywhere on HULU. Reese Witherspoon has also started a book club, which selects books with female protagonists. Many of the books then go on to become films or TV series.

Not only do diversity and gender research constitute a decisive factor vis-à-vis the quality of the art history and museum collections of tomorrow. They also represent a fascinating challenge for contemporary art theory, research and genre descriptions. But art museums are not just for the geeky professionals who work and exhibit in them. Museums of historical and contemporary art are among the nobler parts of our society’s intellectual life, and can help mobilise a sustainable democracy rooted in equality and freedom.