Museums Abroad Are Rethinking Themselves. But Something's Rotten in the State of Denmark?

Column published in Kunsten.nu - 5 July 2023. By Augusta Atla

Column published in Kunsten.nu - 5 July 2023. By Augusta Atla

The old European art museums are currently restructuring their collections and innovating in an attempt to put an end to gender discrimination in art history. What about Denmark? Are Denmark’s museums asleep? Are we about to end up as a bad example with museums and national collections at a standstill, caught up in a perpetual time warp in the Western world? I recently visited ARoS, the National Gallery of Denmark and Arken to see how things are going.

It's extraordinary how many female artists from the 15th century to the present day have been omitted from the pages of history books and denied their place in our cultural heritage. We aren’t talking about just a few hundred artists around the world; we’re talking about a vast, unknown number of female artists.

Nor are we merely talking about female artists who were prevented access to the upper artistic echelons by the patriarchies of their day, but also – amazingly – about female artists who flew in the face of the status quo and actually achieved success and wealth in their lifetimes. Even the latter were written out of history.

One hugely successful artist, Elisabetta Sirani had to paint in the presence of witnesses to prove it was actually she who was painting. In her day, she ended up as a kind of Bolognese tourist attraction. She painted for such dignitaries as the Roman empress, Eleonora Gonzaga and the Grand Duchess Vittoria della Rovere until her death at the tender age of 27. Even though her works fetched high prices and were highly sought after in her lifetime, it was not until this year – 358 years after her death – that the very first catalogue of her works was produced.

The narrative about a canon of art history based entirely on the works of male artists is not simply a consequence of patriarchy, but also a sleight of hand on the part of that patriarchy.

But now, finally, like some sort of a seismological device that can accurately pick up the frequencies of cultural heritage, Europe is listening to the ancient mechanisms of selection. What are they saying?

“Even though as an artist you’re rich and sought-after in your lifetime, we’ll erase you from history because you aren’t a man. We’ll scrap your work or stuff it away in a corner until finally you end up in private collections or museum basements and no one remembers you.”

There are tons of examples of this process – Marisol, Rachel Ruysch, Lavinia Fontana, Properzia de’ Rossi, Fede Galizia and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun – to name but a few.

In the coming decades, as people gradually become aware of this new category of works – Female Artists from the 15th century to the Present Day (both those who were famous and rich in their lifetimes, and those who were not) – and the artists are archived and integrated into art theory, we will entirely rewrite the classic canon of art history.

Not only in relation to the ‘art history hall of fame’, but also in relation to a new understanding of prevailing genres, new descriptions of genres, new methods of public engagement in museums and brand new criteria for hanging museum collections, and maybe even a new, more incisive look at the fundamental philosophical and ideological principles on which art theory and art history are based. One of these fundamental principles is GENDER.

The many special exhibitions in Denmark and abroad, dedicated either to single female artists or gender themes and groups of female artists, have already provided us with a new version of the canon of art history. How, then, can we ensure that we do not perpetuate our bias and that this category of works does not disappear again from cultural history and the field of art history research? The answer lies in the way in which national museums exhibit works from their permanent collections.

We live in exciting times. Currently the pieces in the complex board game of art theory are being moved around radically, and we are witnessing a major transformation in the way art museums abroad are presenting their collections. Like the Titanic, the ancient narrative of art history has already sunk.

The presentation of works from its permanent collection is the powerful jigsaw puzzle of a museum and art history, and today indifference to gender or racial equality is virtually taboo in any art or cultural institution. As the former chief curator of London’s Whitechapel Gallery said: “A museum would be embarrassed today to have a hang or a show that is composed of 75, 80, or 90 percent white male artists.”

Yes. Those days are over.

The muse of our time

In Greek mythology, Mnemosyne (Greek: Mνημοσύνη) is the goddess of memory and remembrance. With Zeus she conceived the nine Muses: Erato, Euterpe, Calliope, Melpomene, Polyhymnia, Terpsichore, Thalia and Urania. They were worshipped in every area of ancient Greek culture and revered as the source of art, poetry, literature, dance, astronomy and music.

In ancient times, the nine muses had her own cult; that cult is still alive and kicking today. The word ‘muse’ comes from the ancient Greek word Μοῦσαι, which means ‘to sing/put in mind’. The word ‘museum’ – Μουσεῖον – has the same etymological roots: it means ‘the place where the muses dwell’.

The invention of the museum was based on the idea of ‘the building for the source of all art’ (the temples of the muses). Since the French revolution and the inauguration of the Louvre, it has been a building for the people, displaying and archiving the narrative, philosophy, ethics and politics of a culture.

Today, despite the fact that the nine muses were invented in the patriarchal society of antiquity, art museums are in the process of ‘replacing their doors’ – both literally and metaphorically.

Finally they are granting access to all artists and recognising all genders: female artists are at last being admitted to ‘the temple of the Muses’ and gaining a tangible place within the hallowed walls of Western culture.

“The one duty we owe to history is to rewrite it.” (Oscar Wilde)

In Europe, museums and galleries, both large and small, are gradually realising that they must either keep abreast of modern research and the zeitgeist – or perish. Museums in the West are now taking a fresh look at their permanent collections, repertoire, public engagement/interpretation and management structures in an endeavour to reflect the 21st century.

For example, this year London’s National Portrait Gallery spotlighted this huge paradigm shift by curating a completely new hang of its permanent collection: the largest transformation since 1896. It also literally replaced its doors with an enchantingly beautiful bronze work The Doors (2023) by Tracey Emin – three bronze entrance doors featuring 45 portraits of women.

This summer (2023), Tate Britain also implemented a major restructuring, reopening with a totally new hang of works from their permanent collections: a hang that reflects a critique of the methodology of art history and re-imagines it, paying tribute to forbidden contemporary art – impressive, ground-breaking works by female artists.

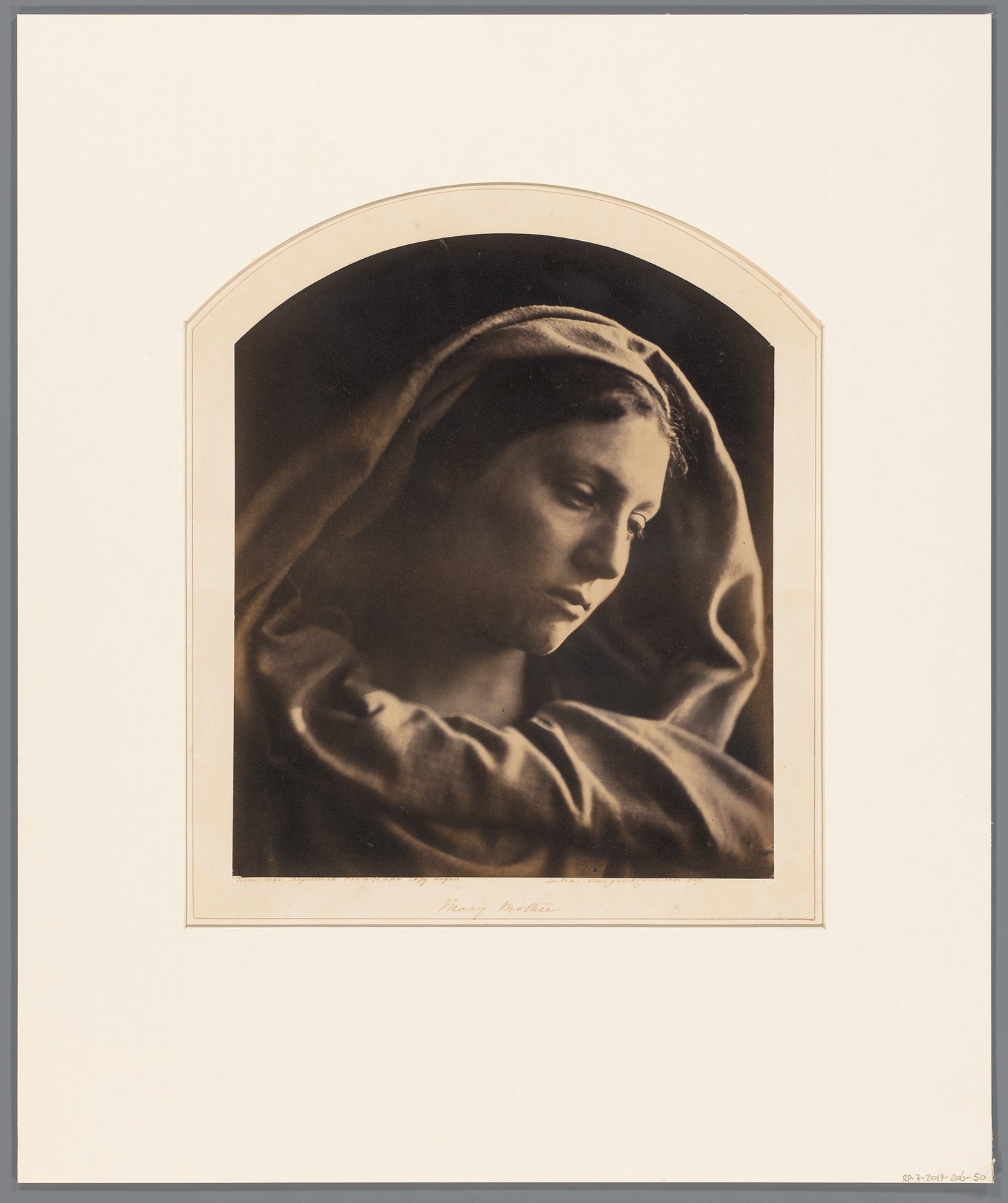

London’s V&A launched the Parasol Foundation Women in Photography Project, which examines the role women have played throughout the history of photography and addresses the gender imbalances that pervade that history. The project features new acquisitions, research, commissions, exhibitions and events.

On louvreguide.com you can book guided tours with an art historian that spotlight female artists in the Louvre collection: guided tours that look at works by such famous female artists as Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749-1803) and Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744-1818).

In 2003, the French state purchased half of Camille Claudel’s artworks and exhibit this collection in its entirety in homage to her importance in the history of French art. In 2017, in the town of Nogent-sur-Seine on the outskirts of Paris, they opened a new national museum, the Musée Camille Claudel, in Camille Claudel’s old childhood home.

In the Netherlands, the Rijksmuseum devised a research programme, Women of the Rijksmuseum, which relates to the museum’s own collection. Started in 2021, the aim of the project is to reveal how female artists influenced Dutch history and the extent to which their heritage is present in the Rijksmuseum’s collection.

This is the first time in the history of the Rijksmuseum that they have made a gender-based distinction in their own collection database. This far-reaching research project involves collecting data on the more than one million artefacts in the Rijksmuseum’s collection. Part of the project also looks at the history of the Rijksmuseum as an institution: it has become clear that female collectors, patrons of the arts and staff played a far greater role than previously acknowledged. The first public result of the research was Women on Paper: an exhibition of about 70 works on paper by female artists.

At the Prado Museum in Spain, a project entitled The Female Perspective involved a survey of all the labels in the museum, resulting, for example, in the removal of all designations such as “wife of” or “was married to”.

That is most certainly something Danish museums would do well to learn from when it comes to Anna Ancher, Anne Marie Carl Nielsen, Anna Syberg, Christine Swane, Alhed Larsen, Lene Adler Petersen and Marie Krøyer. Like the Prado Museum, public engagement/interpretation departments in Danish museums should take a large rubber and systematically erase any label or introductory biography that refers to “married to/wife of”.

The Female Perspective project also includes an exhibition, which is currently running at the Prado. It is a curated exhibition featuring 32 masterpieces from the period 1451-1633 in the Prado’s permanent collection. The common denominator is the fact that all the works were commissioned and purchased by female art collectors and patrons.

The exhibition thus provides a new perspective on history, revealing as it does how female art patrons made a huge impact on the Prado’s permanent collection. Generally speaking, too, the Prado has recently been acquiring new works by female artists: for example, Marcela de Valencia, Maria Blanchard and Aurelia Navarro.

Some years ago I lived in Paris, where I was lucky enough to see the Pompidou Centre’s exhibition elles@centrepompidou (2009-2011). Thanks to the sterling work of the curator Camille Morineau, the museum rehung its entire permanent collection exhibition for two years, featuring work exclusively by female artists. Every single work came from the Pompidou Centre’s own collection. Despite being purchased decades earlier, they had never seen the light of day.

And it is now also four years ago that Tate Britain, for a period of one year (2019), in a wing of their permanent collection, exhibited works solely by British female artists under the title 60 Years.

We can safely say that we are living in a kind of period of upheaval in terms of museum practice, education and archiving within the field of art history. This is nothing to do with being woke or ‘wokewashing’. On the contrary, it’s about attaining greater academic knowledge of how history works/has worked and the ability we now have to survey it with greater awareness.

On an international level, it was back in the 1980s that work began on retrieving works by female artists from the fog of history: that work has intensified over the past 15 years.

So, what about Denmark?

What about Denmark? Why are Danish museums so slow? You’d think that the Tate and the National Portrait Gallery were more portentous, conservative institutions than Arken, the National Gallery of Denmark and ARoS, wouldn’t you?

It’s even weirder, given that Denmark brands itself as the champion of equality.

So, how is it that when it comes to art, compared to other countries and in the light of the zeitgeist, holier-than-thou Denmark is a total backwater?

For the first time ever, the National Gallery of Denmark, ARoS and Arken have female directors – simultaneously. The question is whether they can they raise the standards of the museums to a 21st-century level. Will they succumb to the crippling, age-old approach or pass the zeitgeist test as innovators who will ensure the survival of these museums? Time alone will tell.

The young generation of people and researchers will certainly not accept the fact that we are lagging behind. Even if the art world wanted to return to its dusty old methodology, discussions between people on social media would prevent it.

ARoS has a programme of temporary exhibitions focusing on gender and female artists, but what about their permanent collection? Right now, ARoS’s two exhibitions of works from its collection are hugely outdated. Only 14% of the permanent collection of contemporary art, Far From Home II, features work by female artists. That is, the museum still has to incorporate this new category of work into their permanent collections and their press and communication.

Even though every ten years the National Gallery of Denmark mounts an exhibition devoted to feminism (Efter Stilheden, 2022, What’s Happening, 2015), there’s still a long way to go. Art by female artists isn’t just a niche in art history: works tackling gender and feminism. No. It’s much bigger than that. What we’re talking about is rewriting the history of art in a totally new perspective. The National Gallery of Denmark doesn’t seem to have got that point yet.

Despite new acquisitions of works by Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann and Bertha Wegmann, and the fact that a few works by Anna Ancher, Susette Holten, Suzanne Valadon and Anne Marie Carl Nielsen figure in the permanent collection, there’s still a long way to go. Blink and you miss them. There are still so many works they should acquire and include in the collection.

As for post-1940 works, the National Gallery of Denmark has recently also purchased works by one of Denmark’s greatest artistic geniuses – Sonja Ferlov Mancoba. Not before time! But her works are crowded together like sardines in a can. That is not how the artist envisioned the presentation of her works. Even though Sonja Ferlov Mancoba’s works are fragile and require protection in glass display cases, they don’t need to be crammed together. Just visit the Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens and look at its beautiful collection of Bronze Age art. You’ll see what I mean.

Sonja Ferlov Mancoba’s works require space around them. In terms of form, she explored the primordial forms of history and sculpture like an ancient sundial casting shadows on sand. The Danish artist Per Kirkeby has his own room in the National Gallery of Denmark; why shouldn’t Sonja Ferlov Mancoba? Or even an entire museum like Camille Claudel.

Overall, the National Gallery of Denmark’s permanent collection of works from 1900 to 2018 lacks examples of abstract, surrealist and pop art works by female artists.

Where’s the Franciska Clausen room? And what is the justification for the almost ironically titled ‘Forbidden Art of Wilhelm Freddie’ room, when it was actually art by women that was “forbidden”? Works by Rita Kernn-Larsen were far more forbidden.

It all seems so obsolete. Fortunately, 50% of works in the collection of post-2018 art are by female artists: the only reason I don’t collapse on the floor of these hallowed museum halls with cardiac arrest.

Of the three institutions, Arken seems to be the only one to wish to stay relevant. It is a pleasure to see Laure Prouvost’s work in the entrance of the museum. In general, it seems that the fellow artist Esben Weile Kjær, who curated the permanent collection, actually knows that, especially when it comes to contemporary and recent art, one should account for the gender of artists represented in permanent collections. I left the museum in hope.

Liberté, égalité, diversité! (Freedom, Equality, Diversity)

So, what can museums in Denmark do? Guess what? What museums in other parts of the world are already doing so impressively: set up a national research unit that can track down and archive this new category of works. Give the exhibitions of works in their permanent collections a makeover. Allocate rooms in the permanent collections to female artists. Open brand new museums. Dedicate brand new chronological wings to the new category (women artists from 1400 till today) in permanent collections. Continue – or start – counting gender in their annual programming and acquisition. Commission new permanent works for their architecture like Tracey Emin’s new work at the National Portrait Gallery. Rethink all their public engagement and interpretation activities.

What about following the Pompidou Centre’s example? Cut the permanent collection for a few years and create a chronological picture of only female artists in Denmark (and from abroad) from the 17th century to the present day?

There could be brand new hanging themes in the permanent galleries: ‘Art History Rethought’, ‘A New Canon of Art’ or ‘Our Time of Upheaval’.

They could also create guided tours, using red dots, a map, an app, a flyer and an audio guide, directing visitors to all the works by LGBTQIA+ and female artists. It would make visitors aware of the fundamental principle of GENDER in the history of art and show that museum experts are keeping up with the times. And yes, why don’t the National Gallery of Denmark, Arken or ARoS have a Women and Art theme on their websites like the Tate?

Gl. Holtegaard, an exquisite art centre north of Copenhagen, is threatened with closure. Why not transform it into a museum dedicated to some of the female artists who don’t yet have their own museum? Anna Ancher, Marie Krøyer, Anne Marie Carl Nielsen, Rita Kernn-Larsen and Sonja Ferlov Mancoba etc. Gl. Holtegaard could even serve as a national research unit for all cultural heritage and art museums, and universities, devoting its efforts to this particular undiscovered category of works: female and LGBTQIA+ artists. Gl. Holtegaard could even be the only research library in the country for this new category of works. Currently there are no libraries in the country with an exclusive shelf for this new category.

We’re living in an age and facing a future in which diversity, gender history and gender studies are and will be fundamental to, and totally common in our culture and new normal.

But when I left the three above-mentioned museums, I asked myself: “Why are we so backward in coming forward?” What are we afraid of? Why are we so cautious?

Right now, what we should be afraid of is lagging behind and ending up in a time warp as a bad example. We actually need to take serious, comprehensive, rapid and radical new steps to keep up with the times.

“The message is pretty simple,” says Nicholas Cullinan, Director of the National Portrait Gallery. “If as a national institution you want to grow and thrive, you need to serve your audience. If, for whatever reason, you only represent a narrow group, you will become irrelevant. That’s how it is for any organisation or museum or company.”