Men are also muses for female artists

Opinion piece in Berlingske. 21 September 2024. By Augusta Atla

Article by Augusta Atla, 21st September 2024. Berlingske (published in Danish)

We live in a culture of perfection, to an extent imported from Hollywood, at a time when social media shackles us to indifferent, exquisite, pleasurable aesthetics. We learn to worship what is unreal, foolish, vacuous and distant. We become apathetic: not even the fight for values can rouse us anymore. The picture postcard image is our Valium; we are all victim to the poison that seeps through our veins. In a digital age, where we have lost any human connection – an age when freedom of expression is yet again under pressure, partly due to the reintroduction of the anti-blasphemy law in Denmark (which also restricts Danish contemporary art) and the global censorship of art in SoMe (META) – we need to remind ourselves of the inner passion, the rebelliousness, artistic freedom and closeness that exist amongst people.

To Touch the Existence

That is why the connection between the artist and the muse is once again relevant. Artists had passion, fervour and closeness in their fight for artistic freedom, free sexuality and freedom of expression. Not only in their actual works, but also in terms of an artistic methodology, in which life and work were symbiotic. Like the collision of two stars, human relationships, create vital works of art for posterity.

The artists who had muses wanted to depart from form; they wanted art to tackle existence. Their artistic thesis was inextricably linked to their desire to change the world. The connection, the energy cable, between the artist and the muse was not only methodology, but also an ideal: an ideal which claims that poetry is everywhere, constantly. As Vincent van Gogh put it: “There is nothing more artistic than loving people.”

But the artist and the muse are not merely a great love story: we are talking about a pact that took art and society into account. Hand in hand, those artists and their muses challenged the values of the zeitgeist, undermining social conventions and sexual norms with their own lives as manifestos.

Outdated Myth About the Muse

If you write on Google, “Is muse gendered?”, the answer is: “Even when not eroticized, the relationship between poet and ‘Muse’ is a gendered one. Poets are practically all men, and the ‘poet’s voice’ is a male voice: Muses are all women.” The myth of the male artist or writer and his female muses is misguided and obsolete. I too have had muses, male muses – for about twenty years – and other female artists in history have also had human muses.

What we lack is an entire anthology about female artists and their male muses.

In Greek, Mnemosyne means ‘memory’, personified in Greek mythology as the goddess of memory, who conceived the nine muses. The nine Muses, worshipped throughout ancient Greece, were described as the source of art, poetry, literature, dance, astronomy and music. In antiquity, the nine muses were an inspiration for art and science. Likewise today, the human muse cannot exist without a work. The goddess of history still lives as an idea in ‘the artist and the human muse’: the notion that a work is created for posterity.

The Life of the Artwork

The word muse comes from the ancient Greek verb ‘to sing/ to have in mind’. The nine muses of antiquity had their own cult. Today the cult is still very much alive, the word ‘museum’ comes from the ancient Greek word »μουσεῖον« meaning ‘the place where the muses dwell’. In other words, the art museum as a word and invention is based on the idea of a building dedicated to learning and art.

Today, the art museum is a house for the people, reflecting and archiving the ideas, philosophy, ethics and politics of a culture. Not only does the artist who uses muses dedicate their work to this ‘democratic building for people’, the work co-exists with the muse.

The presence of the muse gives licence to formulate the uncensored. The muse gives the essential permission that carries the work into the zone that would normally have been destroyed in the deep well of inhibition.

In this respect the muse is so powerful, as its existence authorises the alterity of the maker and their work. The muse gives licence to the artist to enter the land of the unknown in their art.

The muse is the ‘green light’ for free speech and artistic freedom. In other words, not everyone is fit to be a muse: it requires enormous freedom, courage and curiosity, as well as the willingness to walk hand in hand into a culture's minefield. Like brothers or allies fight wars together, the muse and the artist fight a zeitgeist – together.

The photographer Nan Goldin has muses: for example, her friend Kathleen White. The entire photographic oeuvre of Nan Goldin is rooted in the environment in which she lives, where life and work are inseparable. Nan Goldin’s big sister committed suicide at the age of 18. Maybe that is why she devoted her art to muses and the outsiders of society.

When the Artist Is a Muse

Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller were lovers and muses for one another. They challenged ideas about feminism, women’s sexuality and monogamy by living their lives outside the norm of monogamous marriage. They were not married – a violation of the morals of the time – and had several lovers: a fact that played a major role in Nin’s writing. Divorce separated Anaïs Nin from her father at the age of 10: her father left her mother for a younger woman. Anaïs Nin and her father wrote letters to each other. Literary critics believe that Anaïs Nin’s letters to her father helped create her writing in terms both of form and methodology.

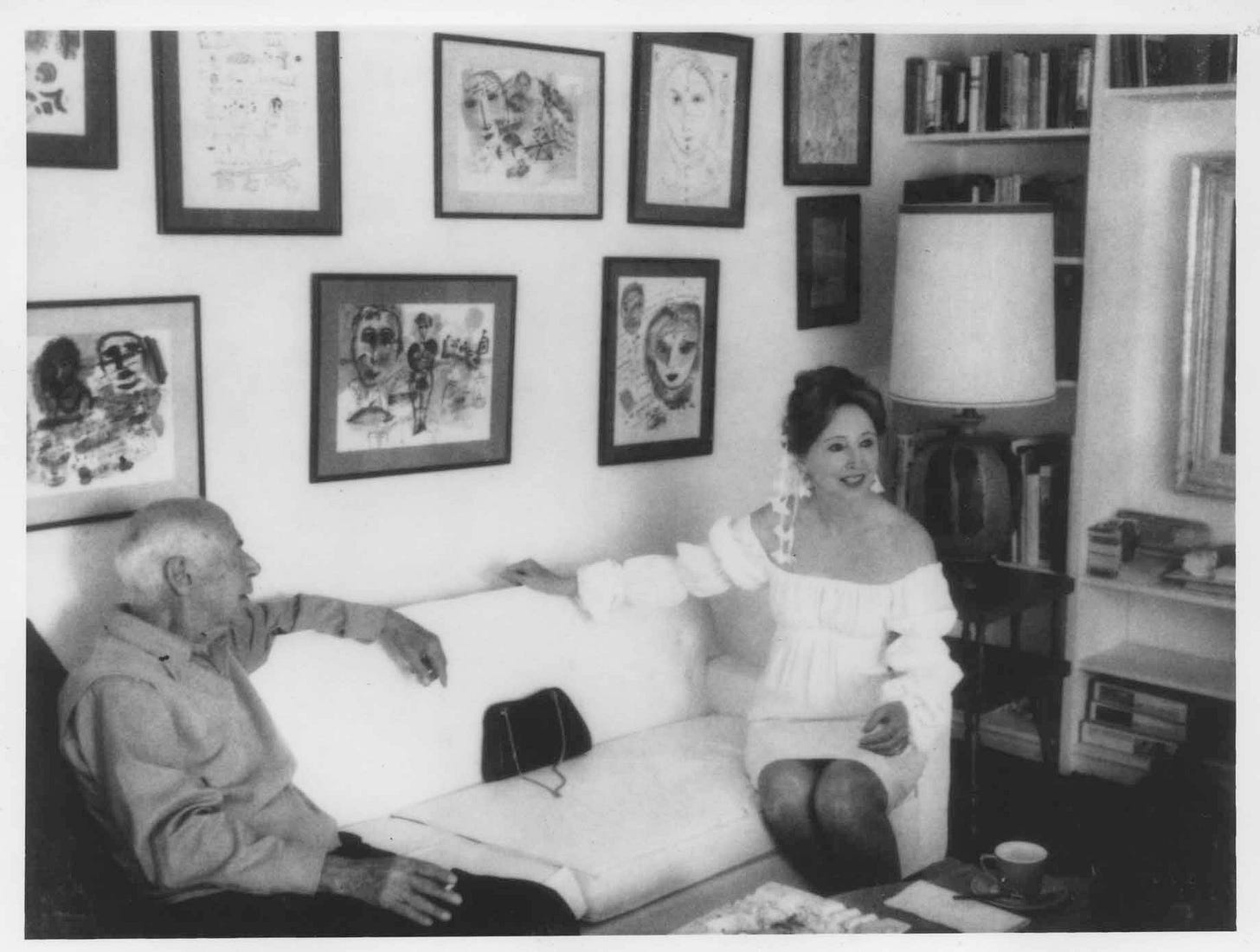

Dora Maar won over Picasso by driving a knife between her fingers in a café to acquire him as her muse. They ended up in a love affair and became each other’s muses in their artistic creations. When they met, Dora Maar was a left-wing political activist. In 1934, she was one of the few women who had signed ‘Appel à la lutte’: a petition for the French to suppress fascism. Before he met Dora Maar, Picasso had never painted a directly political painting. The belief is also that Picasso’s black-and-white tones in his Guernica painting were inspired by Dora Maar’s beautiful black-and-white photographs, which she created in the same studio where Picasso painted Guernica. She had, in fact, found that studio for him.

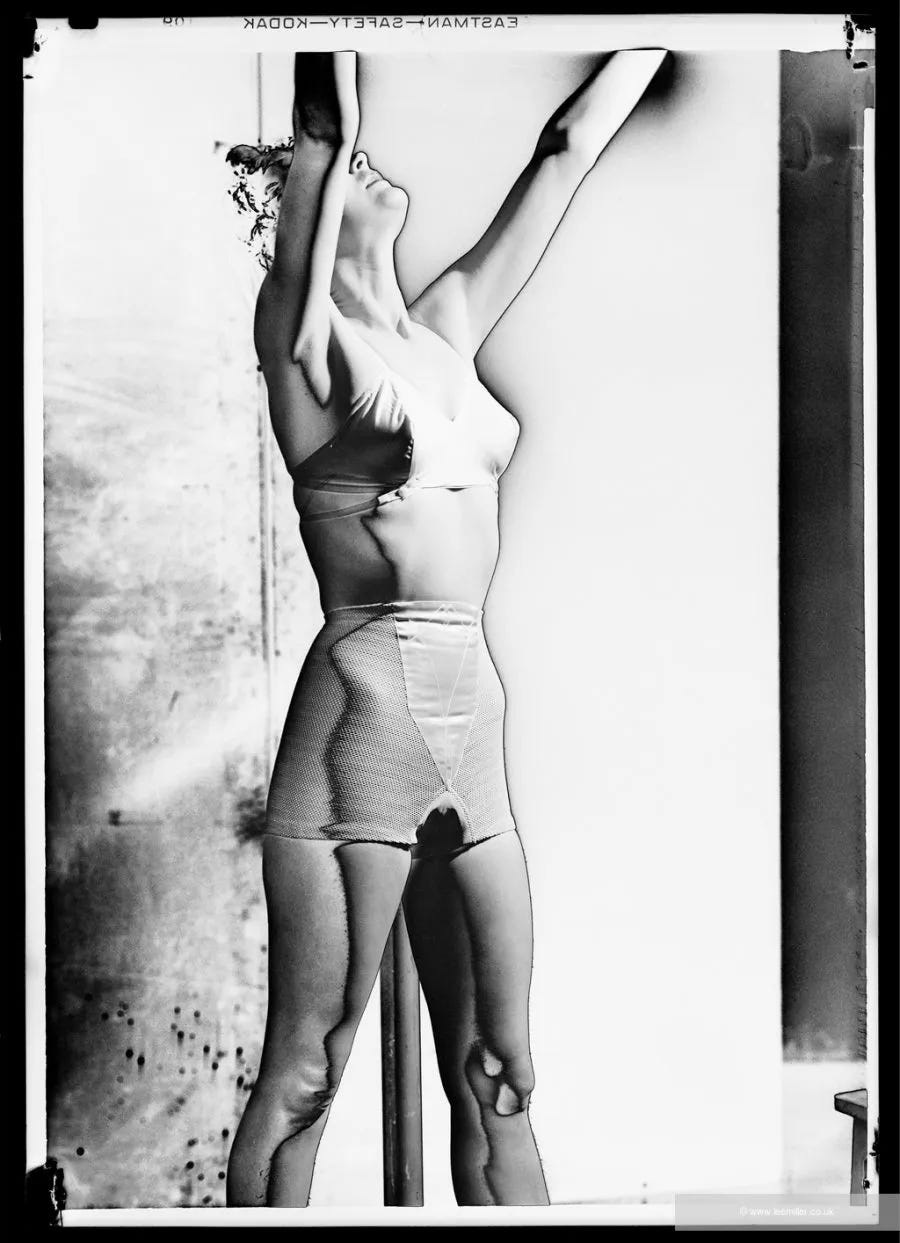

Lee Miller and Man Ray were muses for each other: they lived together in Paris from 1929 to 1932. Generally speaking, we always hear that Lee was Man Ray’s muse; but the reverse was just as much the case. They inspired each other. Myth would have it that Man Ray’s famous solarisation technique first came into being with Lee Miller in the darkroom, where they were developing one of Man Ray’s portraits of Lee Miller. Lee Miller allegedly turned on the light in the darkroom while the photo was in the chemicals and had not yet been developed. This was the origin of the semi-negative image. Man Ray went on to refine and perfect this technique, and became famous for it. A film about the life of Miller, starring Kate Winslet, will be released in cinemas this autumn.

An Intimate Space

These are just a handful of examples. There is also a myriad of examples of gay or bisexual artists and their muses.

In the face of society’s norms, Arthur Rimbaud and the poet Paul Verlaine entered into a gay relationship. Verlaine was jailed for 18 months for being gay, while Rimbaud was exempt for being a minor. Rimbaud’s famous poem about love is about the fact that his contemporaries criminalised homosexuality. Consequently, he questioned love:

“Love...no such thing. Whatever it is that binds families and married couples together, that’s not love. That’s stupidity or selfishness or fear. Love doesn’t exist. Self-interest exists, attachment based on personal gain exists, complacency exists. But not love. Love must be reinvented, that’s certain.”

Putting this in perspective, in Scandinavia, in and around 1890, homosexuality was considered a mental disorder.

The alliance between muse and artist gives rise to an intimate space, in which the artist’s work gets enhanced. It goes without saying that there is an element of risk. Oskar Kokoschka, the Austrian painter, turned his muse, the composer Alma Mahler, into a doll. In this context, dolls were a safer bet: there was no risk of being possessed. A doll is like an unloaded gun.

The merger of art, eroticism and life adds something wonderful to the structure of our experience as artists and to the work of art.

We often spend a lot of time avoiding the merging of the three, choosing only those elements that do not cause too many problems in our lives, thereby omitting those that really stop the world and help the world change.

Those artists who live their art help us challenge society: not only via their works, but also via their own exemplary lives. This spurs us on towards greater freedom.