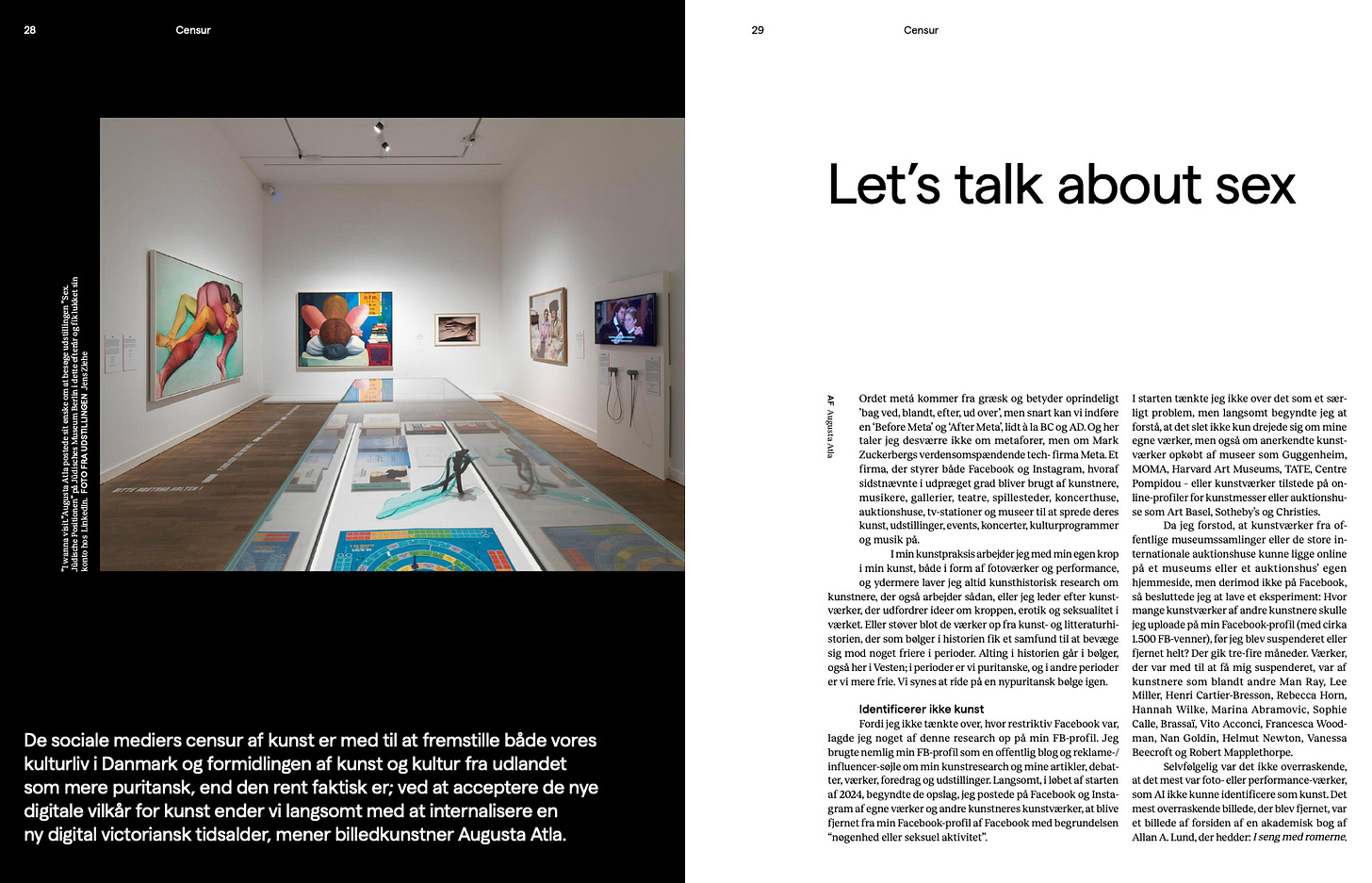

Link to the article in its original language, Danish: Opinion piece in Fagbladet Billedkunstneren. By Augusta Atla

Link to exhibition below: https://www.jmberlin.de/en/exhibition-sex-jewish-positions

The Greek word metá originally means “beyond, among, after, or over.” But soon, we might need to introduce a new epoch: Before META and After META—akin to BC and AD. And no, I am not referring to metaphors, but to Mark Zuckerberg’s global tech conglomerate, META, which controls both Facebook and Instagram. The latter, in particular, has become a vital platform for artists, musicians, galleries, theaters, concert venues, auction houses, television stations, and museums to share their art, exhibitions, events, cultural programs, and music.

In my artistic practice, I use my body as both subject and tool, creating photographic works, drawings, paintings and performances. Additionally, I engage in art historical research on artists who work similarly or on artworks that challenge conventional ideas about the body, eroticism, and sexuality. My research often uncovers historical works that, like waves, have driven societies towards periods of greater freedom. History, particularly in the West, tends to oscillate between puritanism and liberation. Unfortunately, we seem to be riding a neo-puritanical wave once again.

AI CAN NOT IDENTIFY ART ( - not even drawings by Egon Schiele)

Without much thought about Facebook’s restrictive policies, I initially used my FB account as a public blog to share my art research, artworks, articles, debates, lectures, and exhibitions. But by early 2024, my posts—featuring my own works as well as those by other artists—began to disappear, flagged for “nudity or sexual activity.”

At first, I dismissed it as a minor issue. Gradually, however, I realized that it wasn’t just my works being censored, but also pieces by renowned artists collected by institutions like the Guggenheim, MoMA, Harvard Art Museums, Tate, and Centre Pompidou. Even works displayed on profiles of prestigious art fairs and auction houses like Art Basel, Sotheby’s, and Christie’s were being removed.

I decided to conduct an experiment: How many artworks by other artists would it take for Facebook to suspend or delete my account, which had about 1,500 FB friends? It took approximately 3-4 months. The works that led to my suspension included pieces by Man Ray, Lee Miller, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Rebecca Horn, Hannah Wilke, Marina Abramović, Sophie Calle, Brassaï, Vito Acconci, Francesca Woodman, Nan Goldin, Helmut Newton, Vanessa Beecroft, and Robert Mapplethorpe. Unsurprisingly, most of these were photographs or performances—mediums that Facebook’s AI struggles to recognize as art.

The most surprising removal? The cover of an academic book by Allan A. Lund titled I seng med romerne (In Bed with the Romans). Although Facebook reinstated it after I appealed, I was suspended for 24 hours.

On September 11, 2024, I appeared on Danish national radio, DR P1 Kulturen, to discuss Rebecca Horn’s artwork Unicorn (1970)—one of the artworks Facebook had censored. Ironically, DR (the Danish national state tv and radio station) recently withdrew from X (formerly Twitter) to focus on Facebook, couldn’t share that very artwork on its own platform. What are the implications for Danish cultural life when META fails to recognize art?

The issue isn’t confined to Facebook. I tested LinkedIn by uploading the artwork Unicorn—it was promptly removed. Instagram is no better; attempts to post Man Ray’s 1929 photographs also resulted in censorship.

This leaves me with a critical question: If LinkedIn, Instagram, and Facebook are unsuitable for sharing art, where does that leave us as artists? Where does it leave museum directors or even media organizations? Where is our society heading? Where does it leave artistic research and debate?

This censorship undermines not only artistic research but also our understanding of history, feminism, sexual liberation, gender equality, artistic freedom, freedom of expression, and even reproductive rights.

LET’S FORBID ART THAT CHALLENGES?

LinkedIn’s and META’s censorship of art becomes an invisible barrier, slowly presenting both our cultural life in Denmark and the dissemination of art and culture from abroad as more puritanical than it actually is. By accepting these new digital terms for art, we are gradually internalizing a new digital Victorian era. The danger lies in our silence, our failure to recognize what is being suppressed.

I am concerned. Especially if we don’t address it and fail to identify what this mechanism is suppressing in terms of art and culture. That is what I am trying to do here: Let us at least keep our eyes open when the curtains are drawn.

Take, for instance, DR’s chief editor Anders Emil Møller, who justified leaving X on the tv programme DEADLINE (August 5, 2024) by stating, “We are here to engage Danes with our content. Our mission is to create content for all Danes.” Yet he failed to address META’s censorship of art. How can DR engage Danes with Danish culture if the platform itself censors cultural content?

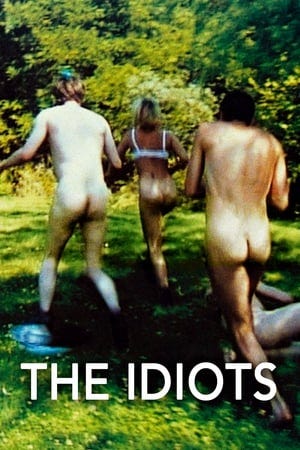

Consider a Danish classic like Lars von Trier’s The Idiots (1998). DR can't share promotional stills from the film on Facebook due to scenes of nudity—even though Dogme films were created to indeed challenge cultural norms.

This makes me think of and remember all the artists who have challenged the sexuality of their time. Where would we be today without them?

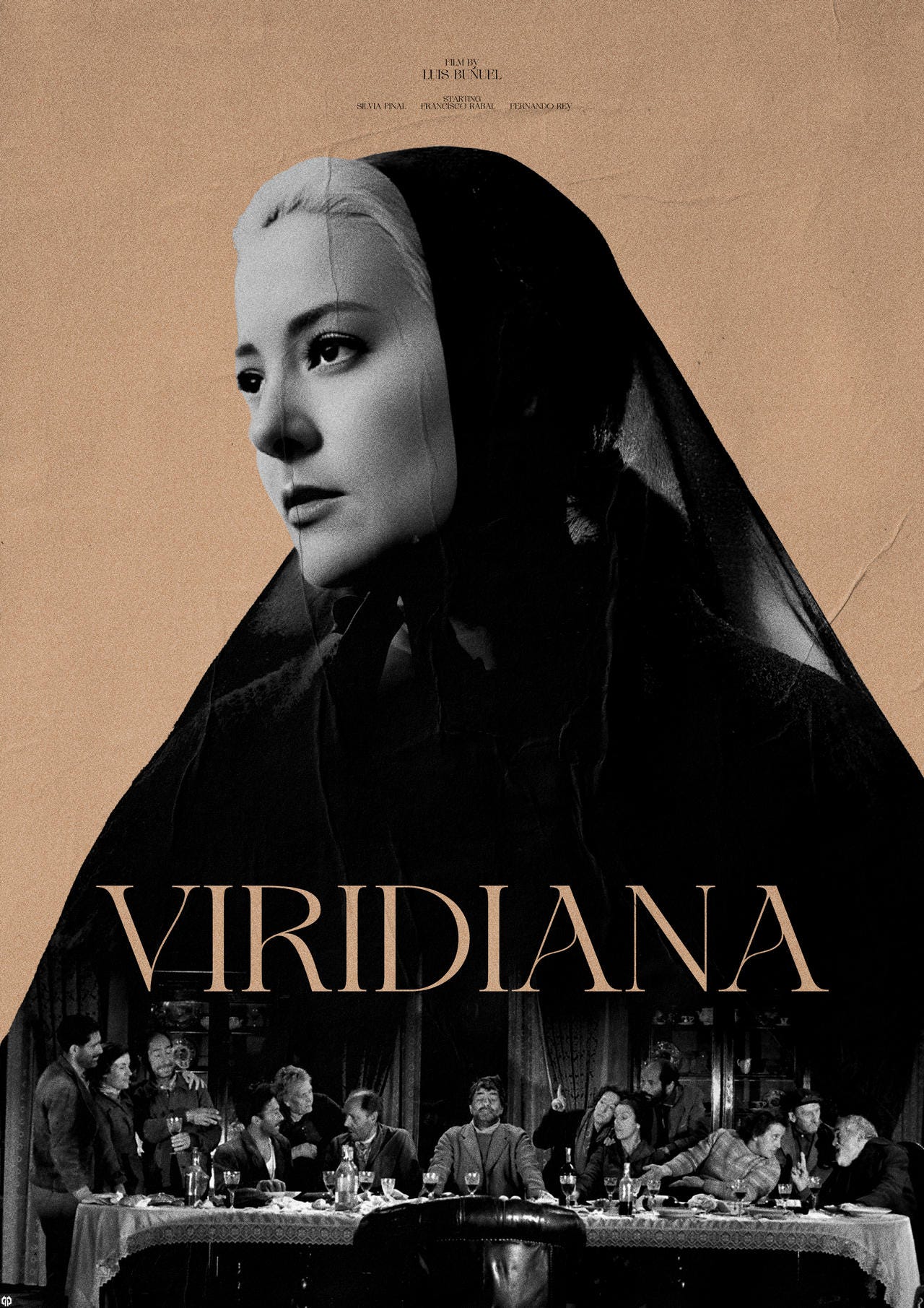

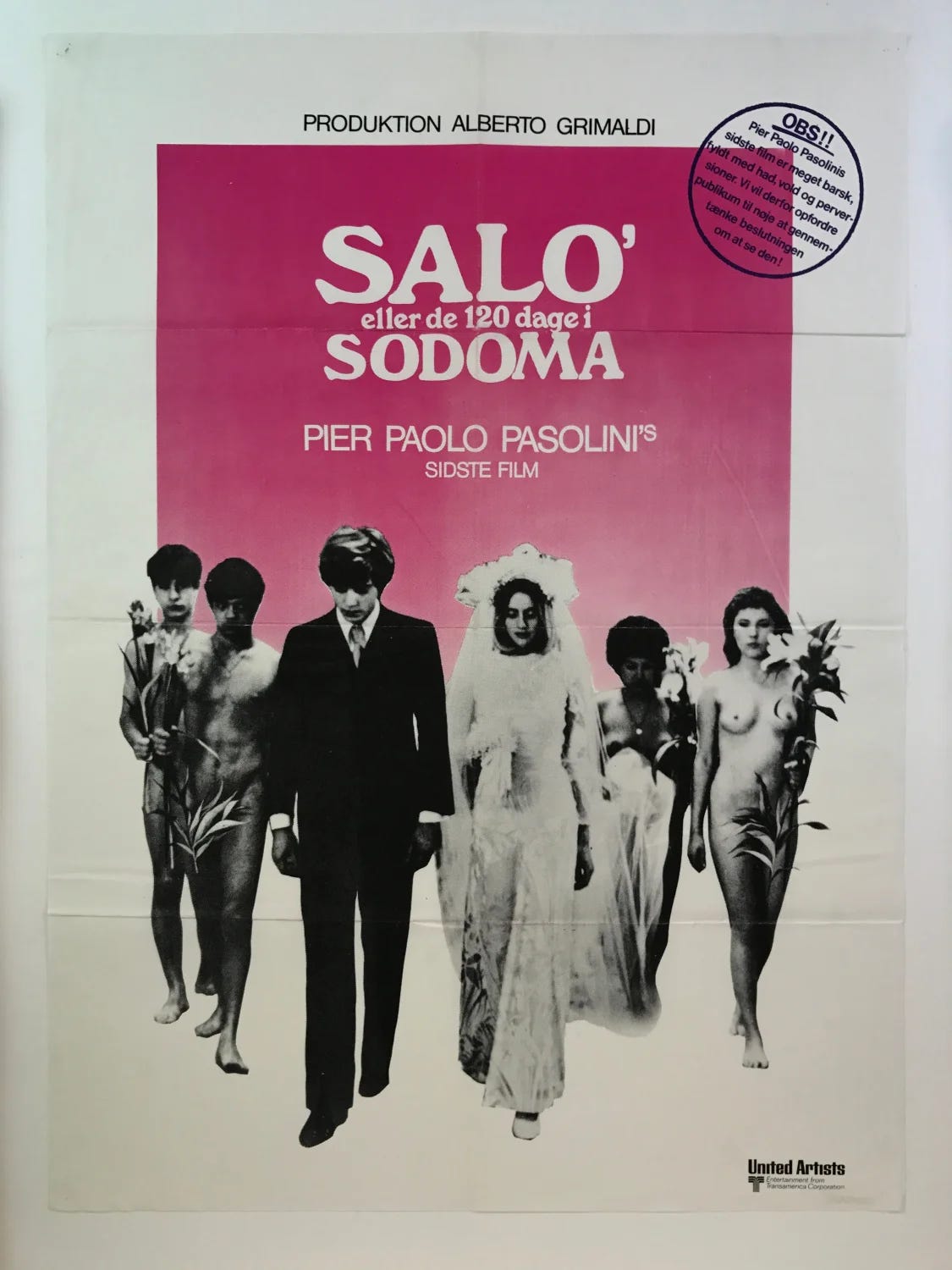

Where would we be without artists who test the limits of a society's freedom? All the works we still live by today, such as Ovid’s literary work Ars Amatoria, which describes the art of seduction in Roman antiquity. Casanova's diaries about his wild life, which eventually led him to prison. Bram Stoker’s horror novel Dracula, which reveals the animalistic sides of humans, transformed into a fantastical tale that has turned the vampire figure into a myth in itself. Federico García Lorca, whose poetry also spoke of homosexual eroticism and his own sexuality, and whose sexuality and poetry ultimately cost him his life. Federico García Lorca was executed by national fascists in 1936. Under Francisco Franco’s dictatorship in Spain (1939-1975), García Lorca’s works were banned. Anaïs Nin’s publications of her diaries and erotic stories, describing female sexual freedom in a time (1934-66) when it was still unheard of to be an unmarried woman or live with someone unmarried. Pier Paolo Pasolini and his cinematic masterpieces on homosexuality and sexual taboos, films like Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), from the Catholic and anti-feminist Italy of the 60s and 70s. Even today, there is still doubt about his death: Who killed Pasolini? Or Luis Buñuel’s divine film masterpiece Viridiana, a story about a beautiful nun, sexualized and desired by a man (her uncle).

Myriads of masterpieces that keep the light burning brightly, even as we, in times like these, choose to extinguish it. The question is: How much light is being extinguished now? After all, social media spans the globe. The future looks dark.

Taylor Swift probably wouldn’t simulate masturbation on stage as Madonna did during her Blond Ambition tour in 1990.

"Dawn united us on the bed, our mouths pressed on the icy jet, blood that never stops flowing." Federico García Lorca