Christ You Know It Ain’t Easy - An Artist’s Thoughts on #inappropriate Art

A contribution to the debate. 18 September 2023. By Augusta Atla. Published in Kunsten.nu

A contribution to the debate 18 September 2023. By Augusta Atla. Published in Kunsten.nu

The bill banning improper treatment of objects of significant religious importance to religious communities is diffuse Alice-in-Wonderland legislation that no one seems to understand or can keep track of. All in all, this law creates huge uncertainty. Even the top lawyers in Denmark do not agree on what it means in practice.

It was no more than three weeks ago that I was high on Greta Gerwig’s success with her film Barbie, seeing the global future as a brilliant, perhaps naive Hegelian symmetry with ever-increasing insight, equality and humanism – especially in the Western world. But happiness is all too short-lived.

On 25 August 2023, the Danish government issued a press release stating that it aimed to: “criminalise the inappropriate treatment of objects of significant religious importance to a religious community.” And with a penalty of up to 2 years’ imprisonment!

Of course, we need to find solutions to prevent certain groups in our society from inciting hatred purely for the sake of hatred. Can I assume, for example, that under the existing law the Ku Klux Klan cannot demonstrate in public places in Denmark?

Politicians can find other measures to tackle racism on the streets, by taking into account the context (the intention). Other countries do: for example, England.

The bill continues and, with the sentence, “The ruling will apply, even if the inappropriate treatment of the object takes place, for example, for artistic or political purposes,” it encompasses art.

It may be impossible to display works in museums and galleries in Denmark. The law goes even further: “Similarly, anyone who, in public or with the intention of communicating to a large group of people, is guilty of inappropriate treatment, will be punished…” In other words, that also means the Internet, TV, books, libraries, streaming, movies and SoMe.

Art soon to be forbidden?

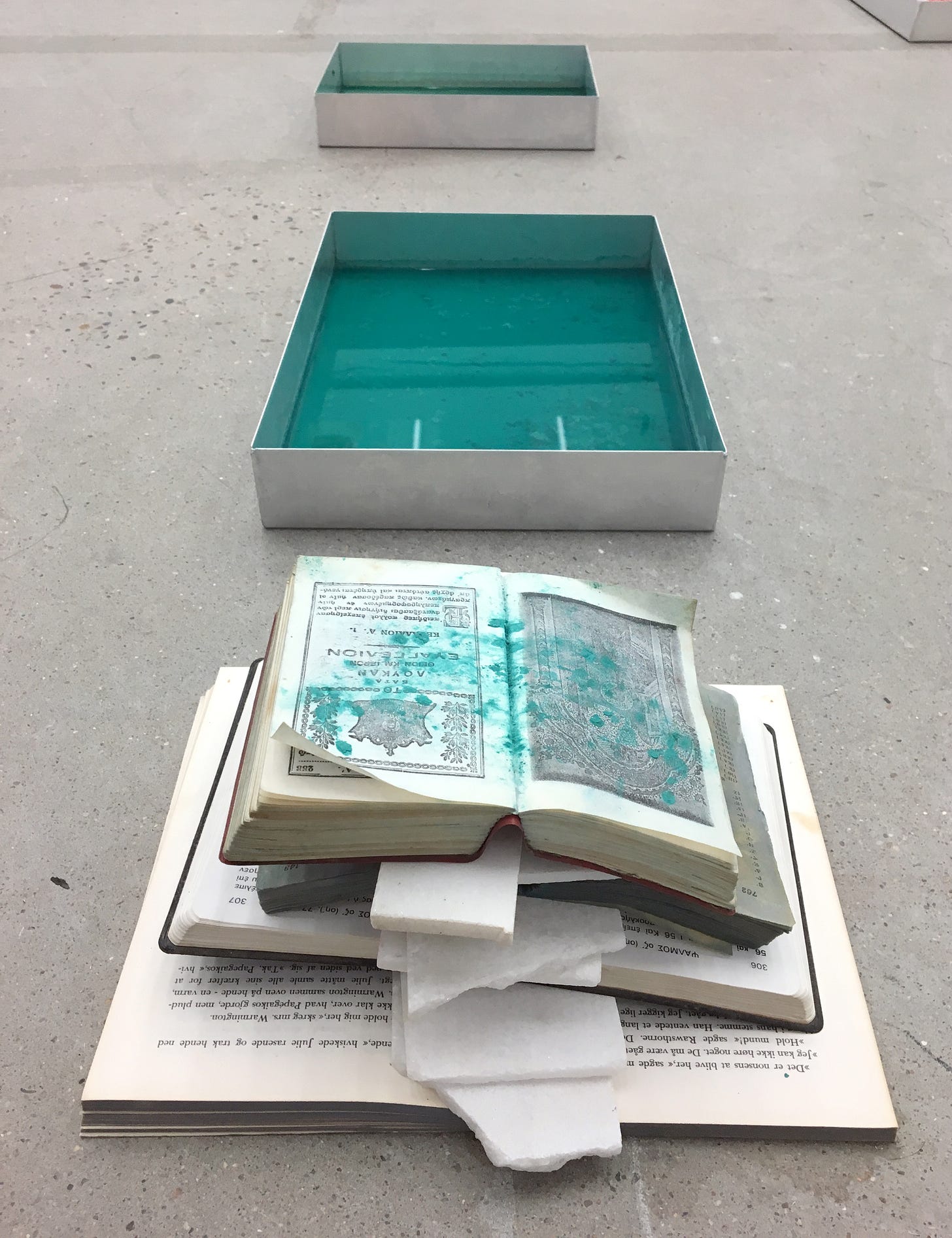

Reading the bill, I realised that my own art practice might be censored. In one of my previous works, I used an upside-down crucifix, and for collages I have used pages ripped out of Greek, Italian and English Bibles, I have also used Bibles as elements in large-scale installations. The reason why for many years my work has involved criticism of the Church is because for centuries, as an institution, the Church – in a lamentable and chauvinistic manner – censored figurative portrayal of the female body, preached a doctrine of heterosexuality and upheld the gender binary. As a result of Constantine’s introduction of Christianity in the Roman Empire in the 4th century, depictions of strong female bodies disappeared for almost 1,100 years. Before Christianity, art featured such images of the female body as the Nike of Samothrace (Winged Victory), which stands in the Louvre, sculptures of the warrior goddess Athena, images of Artemis (goddess of hunting) and the dual-sexed Hermaphrodite.

What is even more important is the fact that the bill could also target a whole string of highly important masterpieces in Western cultural history. In my mind’s eye, I envision my dearest friends (works of art) being cast into the darkness of uncertainty. Both Danish Visual Artists (BKF) and Akademiraadet indicate that the law is founded on an obsolete view of art.

Christ You Know It Ain’t Easy

If we read on, we come across the following: “Prohibition of the inappropriate treatment of objects of significant religious importance to a religious community.” In a larger context, this even casts doubt on the Christian (Protestant) and Enlightenment virtues of self-reflection, education and religious criticism.

As the Bishop of Copenhagen, Peter Skov-Jakobsen wrote in an article in Altinget on 7 September: “Criticism of religion is a gift, so save me from being regarded as fragile merely because I am a believer. Faith also includes criticism of statements and perceptions. I firmly believe that religion is a gift to both Christianity and other faiths. Anyone searching for truth does not settle for a single answer, but continues to open their mind and their eyes to what has not yet been expressed or explored.”

This dialectic is perhaps at the heart of Sarah Lucas’s work, Christ You Know It Ain’t Easy. Or the main feature of the stunning works of Hermann Nitsch, who played with ritual and dogmas to create a Gesamtkunstwerk that exposes the Catholic Church as a theatre.

Viewed in the context of the history of ideas, the law is contrary to the development and direction of Western civilisation. In the latter half of the 18th century, that development was characterised by Enlightenment thinking, which was very much about a critical attitude to the dominant universe of religious thought. The Enlightenment involved a showdown with the fact that authorities and the elite had undisputed power. Although the Enlightenment reflected the writings of great philosophical thinkers, it was also based on the scientific paradigm of the 17th century – empiricism – the thesis that all learning comes solely from experience and observations. Are we now to travel back 300 years in time and promote a dogmatic worldview?

Abuse of power in the name of religion?

As René Offersen suggested in Altinget on 17 September, it may be that, in practice, the bill will only affect burnings of the Koran. But it is no joke when the wording of the law refers to “objects of significant religious importance to a religious community”.

How can a law promise that it is not a law (for some faiths)? There are more than 4,000 religions in the world. How are we to make sure that art does not offend 4,000 world religions? There is no way we can monitor that – even if we wanted to.

So, artists can no longer make “inappropriate” use of Homer’s Iliad in their works, because it will offend the Aeonic religious community in Denmark.

Take the current exhibition at Louisiana devoted to the political artist group Pussy Riot. Will it never be possible to present it again after this legislation comes into force?

In an article in the major Danish daily Politiken on 17 September, Jørn Vestergaard, professor emeritus of criminal law, wrote: “The cross as such suffers no damage when someone takes action in front of it.” Consequently, he does not believe that, going forward, Pussy Riot risk being punished if they choose to perform a similar action in a Danish church.

But has Jørn Vestergaard forgotten that in Denmark we do not only have Protestant churches? There are also the Russian Church and the Catholic Church: both of who have architecturally beautiful buildings in Copenhagen.

Criticism of the Church as an institution only arises because the church is not and never has been as holy as it claims. For centuries, the Church has committed murder, paedophilia and rape, and not only stolen, but burned beautiful works of art. That includes works by the great Early Remaissance artist Sandro Botticelli, who had to content himself with painting pictures reflecting the narrative of the Church – pictures of the Virgin Mary, for example.

Certain Muslim scholars in the world even talk about opposing anti-blasphemy legislation, since it can be abused for repressive purposes and human rights violations, and even misrepresent the text of the Koran.

This bill could soon legalise abuse of power in the name of religion.

Art is the prime shield of democracy

Ever since Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment(1790), the art object has essentially been regarded as functionless. This is what makes art beautiful. It means you do not simply make a work of art so that the viewer can have a great time and go home feeling de-stressed. Or that you ‘merely’ use an art object for direct, literally political or activist purposes.

High art is rooted in free thought and the analytical approach on which our secular society and science have been based since the Enlightenment. This means that art can be critical without being directly for or against anything. An artwork can even be both for and against something at the same time. Art is a way of perceiving the delicate shades of grey and reflecting on ambiguity, training us to see a myriad of different nuances.

Even though a work of art does not directly tackle a political subject and is ambiguous, the very fact that art is rooted in free expression makes it outrageously political. In other words, art is one of the cornerstones of a functioning democracy.

The Achilles heel of this law

So, the question is whether Madonna should be sent a list of religious symbols and an explanation of #inappropriate, before she builds her set on the stage of Royal Arena Copenhagen on 25 October, when she comes to Denmark with her Madonna Four Decades, The Celebration Tour. After all, she is famous for classics such as ‘Like a Prayer’ – a music video that features burning crosses.

The Ku Klux Klan also use burning crosses. But everyone knows that Madonna’s art is about the polar opposite: diversity. This is a good example of how we need to view an action in its context: you cannot legislate yourself out of it with symbols.

We need to legislate differently, dealing with the context and the intention (racism). That way, the law will not impact art.

I assume that the Danish legislation already takes into account that one may not publicly incite or promote hatred towards other citizens on the grounds of their faith, ethnicity, sexuality, disability or gender. Could one not simply apply or tighten up that part of existing legislation that tackles racism?

I agree with Akademiraadet who in their statement in opposition of the bill “warn against the unintended consequences of the bill”, recommending instead “a tightening or clarification of existing legislation.”

My absolute favourite works in the history of art

How many artists throughout history have not helped us understand ourselves, turning upside down every stone of our cultural heritage? That tradition continues to this day.

We owe everything, especially now, to amazing artists such as Sergei Parajanov, the Armenian film director and screenwriter who was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment by the Soviet authorities.

And what about a beloved, yet incredibly blasphemous work of art like Monty Python’s Life of Brian? Can it no longer be screened in Danish cinemas? And would a new, potential, future, Danish genius à la John Cleese be able to make his works at a Danish film school?

What about the new Danish geniuses of tomorrow, following in the footsteps of Lars von Trier? Is the latter’s film Antichrist now banned? What about Rosemary’s Baby by Roman Polanski, a film based on a book by Ira Levin and dealing with a blasphemous topic of Satanism? Or the classic film Viridiana by Luis Bunuel, which is all about incest and blasphemy?

What about Benedetta: a relatively new film that tells the story of the lesbian nun? Or the great cinematic work of Pier Paolo Pasolini based on one of the Marquis de Sade’s books: Salo?

The proposal covers not only new actions: the ban will also apply to the retransmission of programmes featuring improper actions. It makes me think of a beautiful work by Bjørn Nørgaard and Lene Adler Petersen – The Female Christ. Can it no longer be displayed in the rooms of the National Gallery of Denmark? Or on their website? I do not believe there is a clear-cut answer anymore. The same can be asked of Danh Vo’s work Oma Totem (2009).

Take the stunning, incredibly famous work by Basquiat that features a skull and a cross. Will this be banned from catalogues and his catalogue raisonné and from the shelves of libraries throughout Denmark? Or reprinted in a Bruun Rasmussen sales catalogue, were they lucky enough to be auctioning that work.

And what about fashion photo and design classics by John Galliano, Helmut Newton, Christian Dior and Versace?

Will design, film and art schools be expected to outline this new potential censorship in their curriculums? I am confused. The bill also includes “lifelike copies” and “props” that could “be confused with the originals”. In this respect, this law could end up restricting the historically accurate representations of history in films and the performing arts.

Even though Francis Bacon’s early work Crucifixion (1933) may be exempt from the law because it is a painting nevertheless there is something vague about the law: “Nor, generally speaking, will it apply to drawings, paintings, figures etc., unless in themselves they are of significant religious importance to the religious community: for example, the Catholic crucifix or the Judaic mezuzah.”

Ai Weiwei is another artist who proves that certain things in art are aimless, mocking and ruthless. Our society must be able to withstand beatings. Otherwise we will develop a culture of silence, which in the long run will render us unintelligent, paranoid and foolish.

After all, who knows what #inappropriate means?

One glaring example of art censorship in history was the Nazi definition of ‘Degenerate Art’: works of art that were an “insult to German feeling’. Works that did not support the cruelty of fascism, which recognised neither diversity, humanism nor diversity.

Accordingly, it also goes without saying that the AICA has rejected the bill with its current wording. The AICA us the Danish section of AICA International, Association Internationale des Critiques d ‘art, founded in 1950 with the aim of rekindling critical discussion about art that had been stifled by the fascists during World War II.

The organization is under UNESCO protection and has more than 4,500 members throughout the world. One of AICA’s key mission statements is “… impartially defend freedom of expression and thought and oppose arbitrary censorship.”

In fact, for the same reason, 77 intellectuals throughout the world have spoken out against Denmark’s new bill.

Last but not least, this anti-blasphemy law in Denmark means that not only artists, but also leaders of art institutions will internalise their doubts.

A recent article in Politiken describes how even the police have their doubts. The uncertainty alone means that all of us involved in the art industry will end up getting well and truly confused, and that the art industry will lose power and finally become destabilised.

If this law comes into force, I will not know whether I am living in Russia, the Middle East, back in World War II or in Tunisia. But what I do know is that an old and incredibly far-reaching term will have been revived: art police.

Follow: @kunstneriskfrihed_dk

Augusta Atla is a visual artist and columnist for kunsten.nu